COP30 ends with mixed climate deal in Brazil

More money for adaptation, no firm fossil fuel phase-out

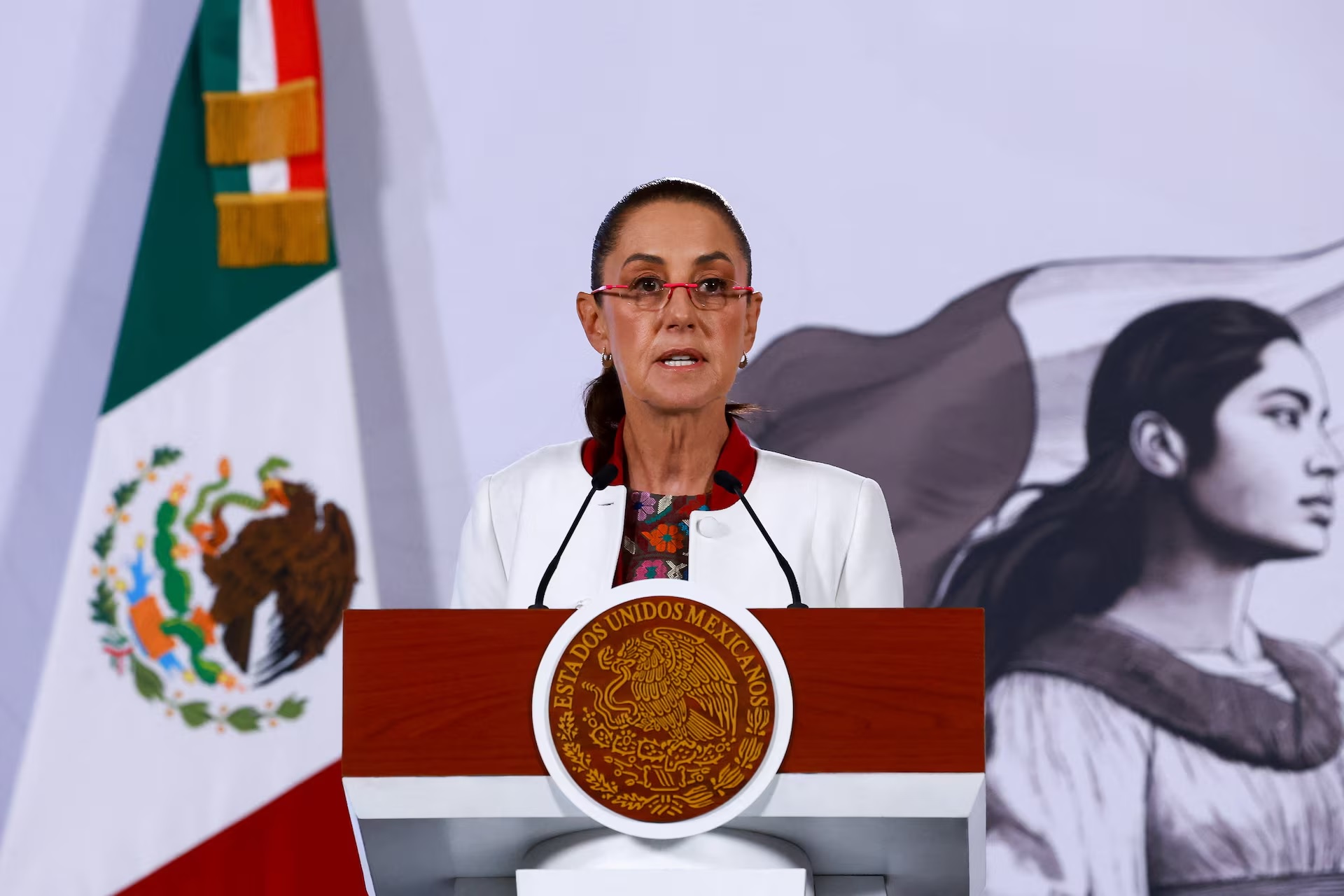

Two weeks of intense negotiations in the Brazilian Amazon have produced a climate deal that is being described as a fragile compromise rather than a breakthrough. Delegates at the U.N. COP30 summit in Belém agreed to boost funding for poorer countries to help them adapt to rising seas, harsher heat waves and more destructive storms, according to the Associated Press. The outcome builds on last year’s “loss and damage” fund by adding clearer promises of fresh cash, though concrete numbers remain vague and many details are left to future meetings. For vulnerable nations that came to Brazil demanding firm timelines and binding promises, the result feels underwhelming.

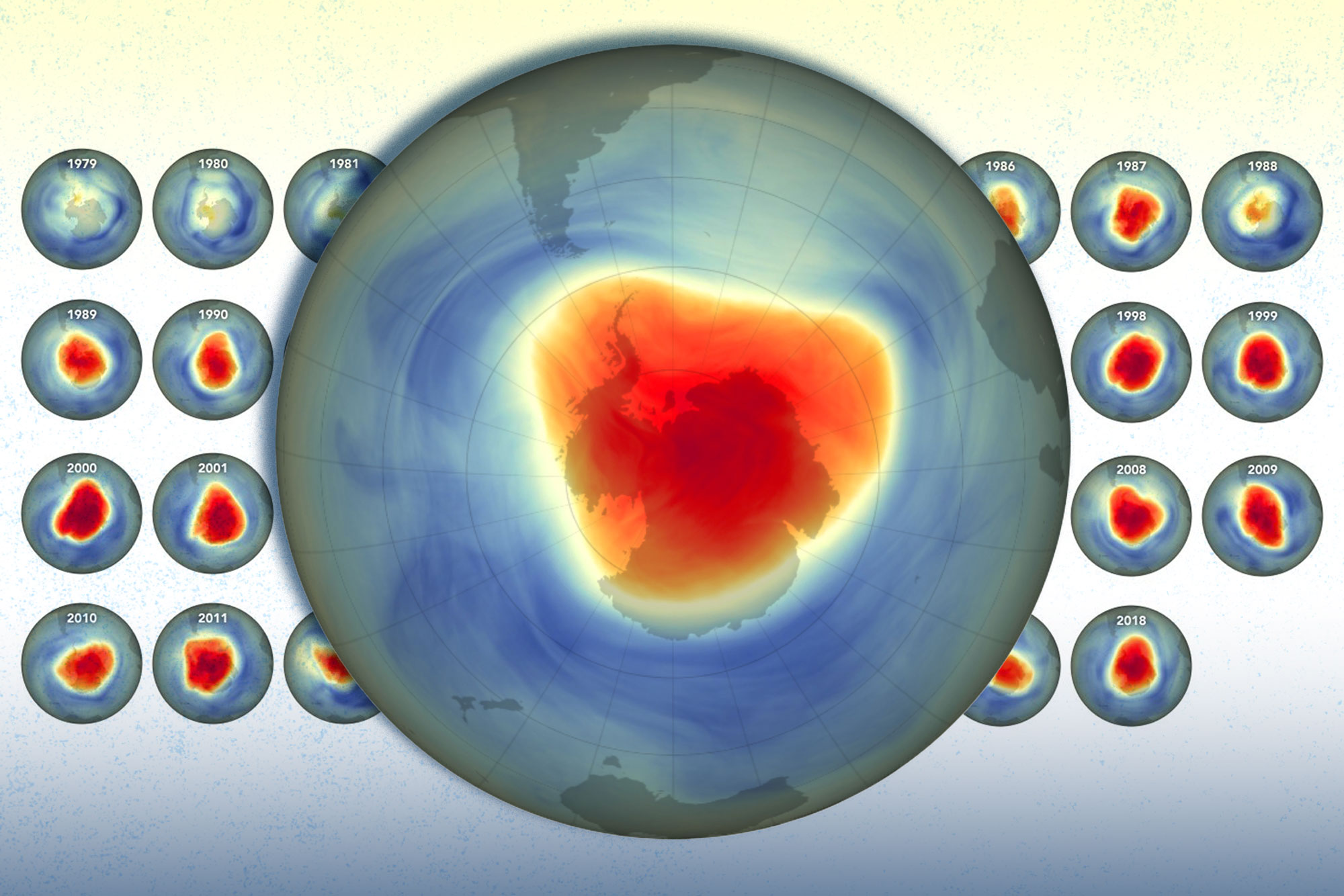

Where the agreement is weakest is on fossil fuels. Governments endorsed language about “scaling up renewables” and “reducing unabated fossil-fuel use,” but stopped short of calling for a managed phase-out of oil, gas and coal, something scientists say is essential to keep global warming within 1.5 degrees Celsius. Major producers argued that abruptly abandoning fossil fuels would threaten energy security and economic stability, while activists and Indigenous leaders accused negotiators of bowing to industry interests. The talks were also disrupted by a small fire at the venue, a symbolic reminder, campaigners said, of the risks of staging a crucial climate summit in a region under pressure from deforestation and extraction.

What the deal means for the next climate cycle

Despite the disappointment, the Belém outcome does contain building blocks for future action. The decision wraps up the current round of the global “stocktake,” acknowledging that the world is badly off track and urging countries to tighten their national climate plans before the next summit. It outlines new work programs on adaptation, early-warning systems and climate-resilient agriculture, which could steer aid toward communities already facing crop failures, floods or deadly heat. Supporters say the text keeps the multilateral process alive at a time when geopolitical tensions—from wars to trade disputes—could easily have derailed progress altogether.

Critics, however, worry that the lack of clear deadlines or enforcement tools will encourage governments and companies to keep approving new fossil-fuel projects while talking about distant green targets. They note that many of the promised financial flows remain voluntary and subject to budget politics in donor countries. Still, the final hours in Belém showed that a broad coalition—from small island states to some large emerging economies—now openly backs a fossil-fuel exit, even if they could not secure the words “phase-out” this year. That signals where pressure is likely to build before the next round of talks, as courts, investors and voters increasingly demand that climate diplomacy translate into real-world cuts in emissions.