Sheikh Hasina’s Shuttle Visit and “Ivanka”, “Putul” Diplomacy

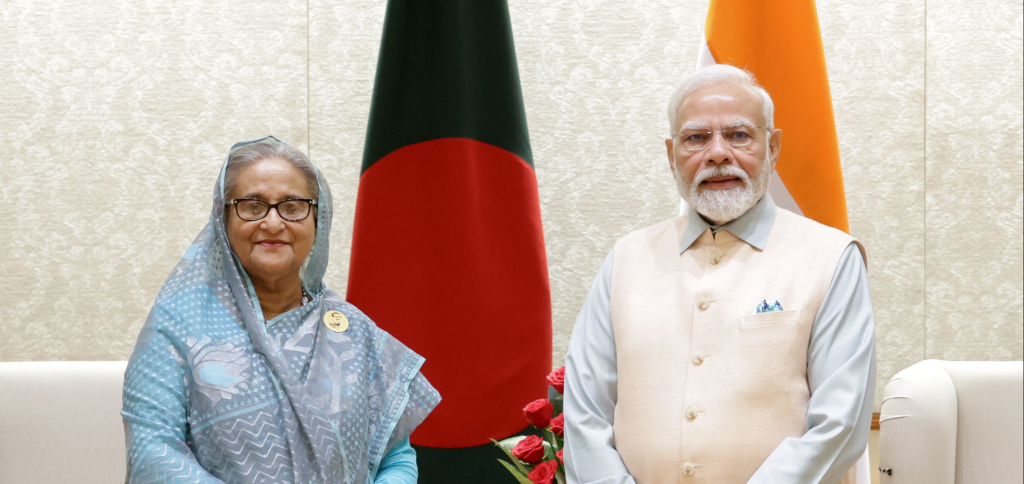

Sheikh Hasina, the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, joined the oath-taking ceremony of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s consecutive third term as Premier. In this ceremony, Hasina did not make any comments to the media. However, some pictures surfaced in the press and on social media. In those pictures, two issues are highlighted. One is that Hasina met with the Prime Minister of India and her daughter, Putul. Some Delhi intellectuals commented that it resembled Trump’s diplomacy, as Trump’s daughter, Ivanka, was present at a meeting with the Indian Prime Minister. However, Sheikh Hasina played the card more smartly than Trump because photographs of her with the three successors of Nehru’s family—Sonia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi, and Priyanka Gandhi—appeared in the media. The All-India Congress is a very old friend of Sheikh Hasina’s party, and she is also like a family member of the Gandhi family. After the death of Sheikh Mujib, the Indian government and then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi provided secret shelter to her family. Some people thought this happened due to Indira Gandhi. But the last ten years of BJP rule proved that it was Indian foreign policy; in Bangladesh, their first choice is the Awami League. Ivanka and Putul’s diplomacy indicates that the relationship between America, India, and Bangladesh was established before that of both countries, but Trump and Hasina were more prior.

However, attending the oath-taking ceremony was not a bilateral visit, so nobody expected any outcomes from this visit. Despite that, in the last ten years, those who followed Modi’s diplomacy thought that any surprise could come through the end of Modi’s term, and one did. Modi declared that he would visit Bangladesh next month.

On the other hand, before Modi’s visit, Sheikh Hasina will go on a bilateral visit to India. This visit was fixed before the new government was set in India. Bangladesh and India have many unsettled issues, like the water sharing of the 54 rivers, the Bangladesh-Nepal corridor, and the Bhutan-Bangladesh corridor through Indian land. Besides, there are two new phenomena: China’s money sometimes overtakes India’s position in Bangladesh, and the unexpected situation in Myanmar, which is a close neighbor of both countries.

So, besides the India-Bangladesh issue, some international issues may arise in the two top leaders’ meetings. Not only the Chinese issue and Myanmar but also the Indo-Pacific issue might come up. American foreign policy never changes drastically, but there are many uncertainties and unexpected past events. So, India’s big economy and regional military superpower cannot run without any precautions. They have lost a lot due to unanticipated quick decisions about Afghanistan by the USA.

Despite that, this is a towering time for Modi. He is not only the second consecutive Prime Minister of India three times but is now one of the world’s players, like Nehru, the first consecutive Prime Minister three times. However, the world power game is different between Nehru and Modi. Nehru was one of the leaders of an alliance against any military pact, while Modi is now one of the leading players of the Indo-Pacific military pact QUAD. For the last five years, QUAD has been one of the top issues in the world, despite its progress not being satisfactory to many strategic experts.

However, it is impossible to back out from the QUAD, and some new policies may include it according to Chinese economic policy and others, even the shape of the EU due to the Ukraine war. Moreover, the next U.S. election is in November, and its outcome will influence the attitude of the winning leader of America.

That will also be a short relief for Bangladesh because Bangladesh has an attitude to keep away herself from this pact, though it is a very tough job. With all the inconvenience, some extra time or unexpected time in diplomacy is always a blessing. It may get Bangladesh into the Indo-Pacific issue, which is also a headache for Bangladesh because of its close ties with China.

On the other hand, besides this international issue, some bilateral issues will come with this short, high-profile visit. Most of them are extensions of some previous MOUs, like health-related ones. Even so, Bangladesh will keep its eyes on a large amount of loans to India and the food security commitments of the Indian government.

A successful outcome will depend on many consequences because the Indian government has just opened its new accounting book, so if they put the first pen and ink on it for Bangladesh, it will be not only unexpected but also significant for Bangladesh in this economic crisis time because Indian loan is softer than China’s loan. Besides, Bangladesh needs loans to build infrastructures towards North East India to join India and Bangladesh’s new economic exploration area.

In this context, the thinking of Bangladesh comes out from that dead issue, which means the issue of the extremisms in North East India. Instead, Bangladesh must move forward with a new economic vision. For example, once, the Assam bottom jute was suitable. Because of partition, the Jute has lost its glory; conversely, due to overpopulation, Bangladesh must focus on producing rice in all the land to avoid starving. Suppose communication between North East India and Bangladesh is going well. In that case, Assam can go for jute cultivation again, and Bangladesh can renovate its lot of jute mills with new technology. Everybody knows that Jute is the best eco-friendly fiber in the world, so this naturally friendly world is the vast market for Jute to produce materials, office partitions, and tools; even the garments from inside cars produce materials, office partitions, and tools. So, this new avenue is knocking these two regions.

The food security issue is vital to Bangladesh and will be more critical. But for the autonomies of the regulatory board of India, it is very tough for India to come to a treaty on it, and previous experience is not satisfactory regarding supply to Bangladesh, which has all the core heart desires of the Indian leaders. So, for food security in Bangladesh, how can India help think in a new way? As a Journalist, I have some observations and thinking, trying to share the people next to another writing.

The high-voltage issue with Teesta River water sharing will probably not occur during this visit. Besides, the reality is that, what I saw last month in the situation of the Teesta River in India part, the two countries must think in a new dimension in this climate change era. Blaming Mamata Banerjee will not be wise, and the two countries must now put their foot on the realistic ground.

The writer is a Bangladeshi National award-winning Journalist and Editor of The Present World and Sarakhon.