The Nation Mourns the Children Lost in Milestone Crash, While the Chief Adviser Smiles On

A training aircraft crashed into Milestone School in Diabari, near Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, due to mechanical failure, resulting in the deaths of many children. The exact death toll remains unconfirmed by any responsible authority. The death of children is perhaps the most heartbreaking of all human tragedies. And yet, accidents are an unavoidable part of life. Just days ago, an Air India crash claimed 260 lives, including newlyweds and children. But a tragedy—no matter how grave—is still an accident.

Disaster Management: A Test We Failed This Time

In accidents like this, disaster management is paramount. Bangladesh has, in many instances, proven its mettle—not just among South Asian nations, but even compared to countries like the United States. For example, during the late 1990s floods that affected vast regions of Bangladesh and parts of West Bengal, a UN body predicted large-scale deaths and food crises in Bangladesh. The country’s administration proved them wrong, maintaining supply chains through remarkably innovative means. Meanwhile, in Malda, West Bengal, floodwaters lingered for six months, and various waterborne diseases broke out.

Since the mid-1990s, Bangladesh’s cyclone management has been widely praised. After a hurricane hit Florida, some international media even suggested the U.S. should learn from Bangladesh’s approach. Following the Rana Plaza collapse, the coordination between the army, RAB, fire brigade, local volunteers, and Enam Medical—a small-town medical college and hospital—was exemplary.

Why Was the Milestone Response So Poor?

Given this proven administrative competence, why was the response to the Milestone disaster so ineffective? Why wasn’t the burn unit or the nearby metro line utilized effectively? Why weren’t the right officials dispatched immediately—those who could arrange essential supplies and transportation?

Victims’ families have shared disturbing accounts of being charged 500 taka for 50-taka rickshaw rides and 600 taka for bottled water that normally costs 60.

The core reason lies in the failure to deploy the actual administrative machinery independently. In addition, the citizens and political workers—those who are usually the most helpful during national disasters—were excluded from the response.

Government Paralysis Rooted in Nervousness

The reasons behind this mismanagement may become clearer upon future analysis, but for now, it appears that nervousness was at the root. Just a week before the Milestone tragedy, the government conducted a controversial operation in Gopalganj under the pretext of protecting a few members of the “Kings Party”—an incident that drew widespread international attention. Some in the government tried to paint the general public in Gopalganj as supporters of the previous regime. But when ordinary citizens in Cox’s Bazar and the Chittagong Hill Tracts responded to the Kings Party in the same way, the administration seemed to panic.

This panic led to severe disorganization and a tendency to withhold information from the public. When a government becomes so internally anxious that it begins hiding facts from its citizens during a national tragedy, public anger grows—and governance crumbles.

Administration Must Be Trusted, Not Sidelined

A handful of advisers cannot manage such a massive crisis alone. Full authority must be given to the professional administration. Those in public service are sons and daughters of this soil. During a national disaster, personal and political affiliations vanish. No one except the depraved considers party lines during death and mourning—and such people are few.

Administrators, too, have families—children, spouses, parents. In moments of tragedy, they don’t just see victims; they see their own. Over the past 47 years of my journalism career, I’ve seen this up close. I’ve learned from their quiet compassion, from their sense of responsibility that goes beyond duty.

The Order That Was Never Given

If the full reins had been handed over to the administration, things would have unfolded very differently. From emergency medical response to funeral arrangements, from lowering flags to school closures and mourning protocols like wearing black badges—every step would have been carried out with discipline and dignity.

The next day, grieving students would not have been beaten in the streets. The police officers who wielded those batons surely did so with a heavy heart—they, too, are fathers, brothers, sons. On a day meant for mourning, even they were emotionally unprepared. But orders are orders.

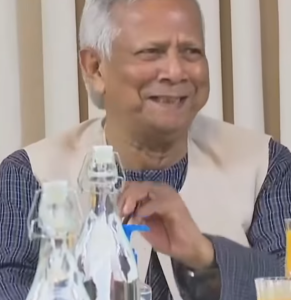

A Banquet That Said Too Much

The images from that same afternoon, when the government met with three registered and one unregistered political party, revealed the full extent of disarray. A nation in mourning—yet no one wore a black badge. Not one.

More disturbing still was the banquet laid out during a meeting supposedly held in memory of the children who had just died. On live television, the only face that seemed to grasp the gravity of the moment was Mirza Fakhrul’s—serious, distant from the food.

The younger attendees, however, were seen eating heartily. Yes, it was tasteless. But can we blame them entirely? The country had recently seen what their meals used to look like on social media. To push away such food, like a child of privilege, was likely not within their means. Their fault? Not really. The real mistake was by those who arranged a feast on a day meant for collective grief.

The Smile That Silenced the Nation

On the day the nation wept, the chief adviser smiled—again and again—during a televised discussion. Everyone saw it. What else is there to say?

In some Hindu communities, feasting after a death is still practiced as a social rite, but several Indian states have made it illegal, recognizing it as harmful and outdated.

Not Just Inexperience—A Failure of Basic Sensibility

The head of government and his aides may be politically untested. But they are not unsocialized. They belong to families too. Was it so hard to understand that laughter and feasting were out of place that day?

Some politicians even arrived at the burn unit with full entourages. These were men who once belonged to student politics—did they forget the ethics of leadership they once claimed to uphold?

Where Protocol Ends and Common Sense Begins

No political leader needed to enter the burn unit. If they wanted to help, they should have joined rescue teams, not paraded through intensive care wards without medical aprons. How is that acceptable?

Watching it all unfold, one can’t help but wonder if our society—our very state—is suffering a kind of psychological decay. Governance now takes place at night, sleep happens in daylight. And to top it all, senior statesmen like Mirza Fakhrul and Amir Khasru must wear ID cards around their necks—like schoolchildren—just to enter government guesthouses for meetings.

Rituals Without Meaning, Systems Without Soul

As a journalist, I’ve met heads of state and government, both at home and abroad. Visitor cards are issued, yes—but they’re handed to protocol officers, not worn around one’s neck like a punishment.

So why, on a day when the loss of schoolchildren should have weighed heavily on every official, were two of the nation’s most respected senior politicians forced to wear ID tags like schoolkids?

And then, at the press briefing following that political meeting—not a single word, not even a perfunctory mention, of the children who died.

Where does our sickness lie? In our minds? In the machinery of governance? Or somewhere deeper?

Wherever it is—don’t we owe it to ourselves to find out?

The Author: Recipient of the highest state journalism award; Editor, Sarakhon and The Present World.