Bangladesh 2026 Elections: Testing the Awami League’s Core Support

Discussion of every dimension of the 12 February election will require the passage of time. Time is a decisive factor in all political processes. At this moment, few possess the mental readiness to absorb the events of the day and night preceding 12 February, the sudden addition of two crore votes within half an hour on election day, and the shifts in international politics in the lead-up to the vote. Most people simply feel that they have been released from prison. Therefore, the iron curtains will not be torn away at once. They will be lifted gradually, as time permits.

Yet the single most significant aspect of this election was the forced exclusion of the country’s largest, oldest, and nation-creating political party from the electoral process. It was not only the party that was barred. Its millions of activists were pushed into flight and compelled to endure lives of hardship and insecurity. Thousands of homes were burned, silencing entire families. Over the past year, more than a hundred leaders and activists of the Awami League have died in prison. Most recently, the valiant freedom fighter of ’71, Ramesh Chandra Sen, was martyred in custody only days before the election. The manner in which he was taken into jail was such that even calling it barbarity would stretch the word beyond its limits.

From well before the official start of campaigning, and for more than eighteen months, these measures were granted a kind of moral license through a repeated refrain that the party in question was fascist and that its leader was fascist.

After 5 August, following what was described as the meticulously designed fall of the Awami League and Sheikh Hasina, the country was inundated with graffiti and messaging. A so-called fascist narrative was systematically constructed. Sections of the media aligned with the government actively advanced that narrative, while other outlets were compelled to comply.

But when the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and the Jamaat, Bangladesh’s natural political opposition, entered the electoral field divided into factions, a realization dawned on the BNP and its international allies. The electoral ground and a significant portion of public sentiment remained under Sheikh Hasina’s influence. The phrase heard repeatedly among ordinary people was simple. We were better off before. In other words, we were better off during Sheikh Hasina’s tenure.

With that shift in perception, the word fascist quietly vanished from the vocabulary of all participating parties. Fifteen months of denunciation gave way to a complete reversal. Even the usually vociferous left withdrew from labeling Sheikh Hasina as fascist. Newspapers that, after 5 August, had vigorously highlighted alleged corruption in development projects under Sheikh Hasina found themselves unable to write even a single line urging voters to support current candidates as an alternative. On the campaign trail, senior leaders, reading the atmosphere, were compelled to address Sheikh Hasina as Apa, elder sister.

Not one party was able to present a genuinely new development agenda. Wherever development promises were made, social media quickly reminded voters that the projects in question had already been completed under Sheikh Hasina, whether in 2012, 2016, or 2017. Deprived of new ground, some were reduced to inaugurating development initiatives for domesticated animals. Such facilities, in fact, have existed at the thana level since the British era.

Meanwhile, the government appeared to anticipate that the Awami League would respond to its exclusion in the manner opposition forces had done in 2014, through petrol bomb attacks, the burning of buses, and the torching of polling booths. From the Foreign Affairs Adviser downward, public statements suggested that any election-related violence would be attributed to the Awami League and Sheikh Hasina.

In the event, the Awami League did not step into that trap. It is an old democratic and politically seasoned party. It recognizes such snares. Through its restraint, it demonstrated that it is neither anti-election nor anti-democratic. It is not a militant organization that kills with petrol bombs.

Instead of violence, Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League displayed what they regard as their true political strength, the strength of the people. Over the past eighteen months, their supporters and activists have, directly or indirectly, lived in conditions akin to imprisonment. In one form or another, they have been confined.

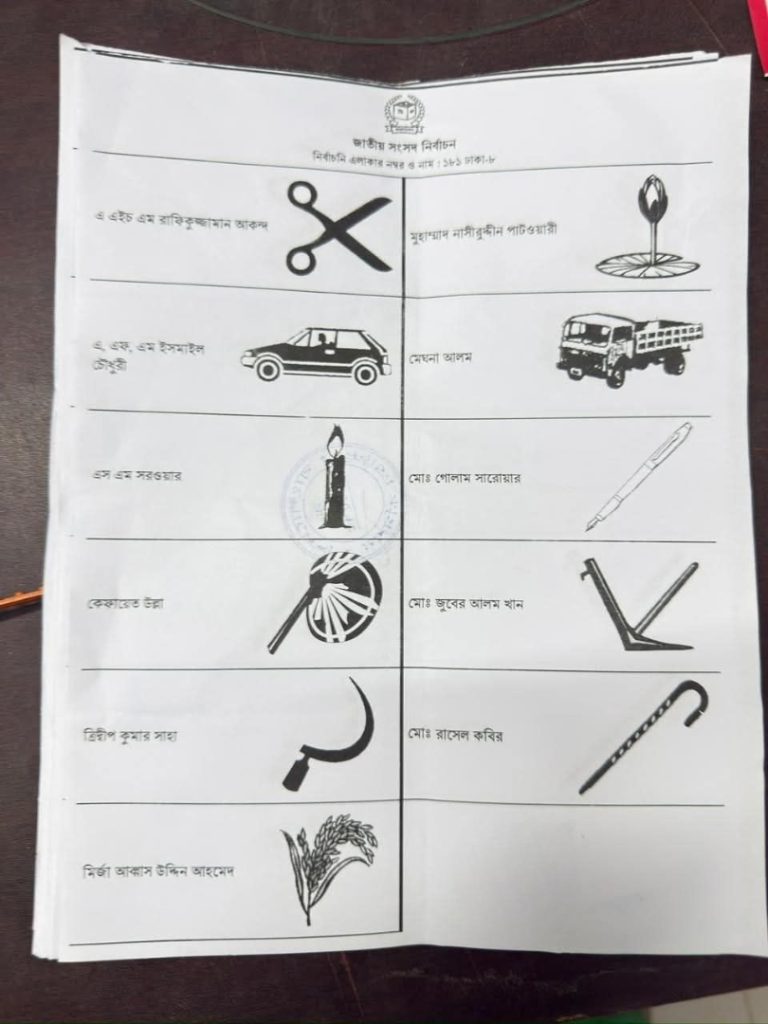

Yet they showed that their political strength remains intact by choosing not to vote. Their symbol was absent from the ballot. Their party was excluded from the contest. Therefore, they did not cast their votes. They were afforded no opportunity to broadcast this message through mainstream media.

Through social media alone, in the simplest terms, the directive reached their activists and supporters.

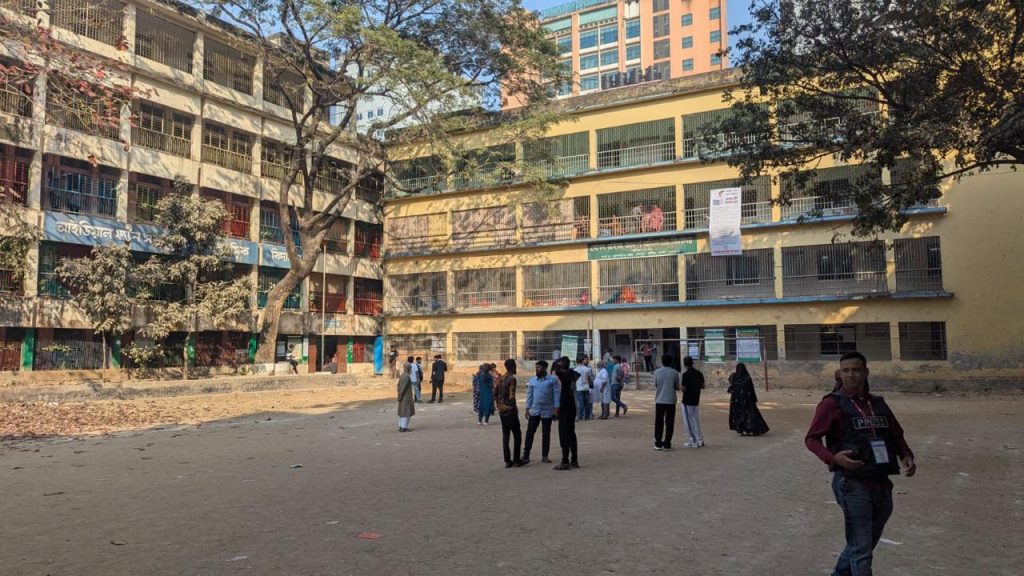

The result was visible. In many polling centers, Awami League supporters refrained from voting. Even those who, under pressure or for personal safety, appeared at polling stations wearing the insignia of other parties often spent the day circulating without stamping the ballot.

The most striking evidence of the effectiveness of this abstention was the reported addition of two crore votes within half an hour, an extraordinary increase apparently intended to raise voter turnout figures.

Whatever further details may or may not surface in time is unlikely to alter the Awami League’s central calculation. Through this election, it achieved its goal. Confirmation that its core vote, no less than forty percent, remains intact. Under pressure, and perhaps for strategic reasons tied to its future political trajectory, only a very small portion of that vote may have been cast. How calculated those decisions were may become clearer in the unfolding political game ahead.

In broad terms, after losing on 5 August to what has been described as Yunus’s meticulous design, the Awami League used the election of 12 February to demonstrate its enduring strength. Those who understand politics recognized how swiftly the party could return to the field and stand again on its own feet. Awami League members themselves were reminded how many feet they possess in difficult times and how essential it is to strengthen them. They have also shown that in moments such as these, one cannot rely upon any feet but one’s own.

In truth, in this election marking Bangladesh’s transition from one phase to another, the Awami League may not have gained more than it expected, but it has certainly not gained less.

The author is a journalist, awarded the highest state honor, and Editor of Sarakhon and The Present World.