Indira Gandhi’s Death Anniversary: The White Saree in the Refugee Camp

Forty-one years ago today, I was standing on the ground-floor verandah of Bulbul Lalitakala Academy in Dhaka’s Wise Ghat when I heard on All India Radio that Indira Gandhi had been shot and taken to the All India Institute of Medical Research.

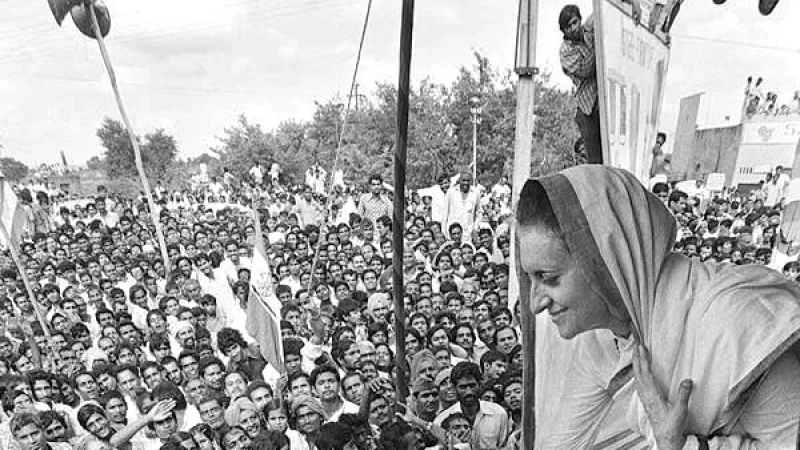

As more people gathered around the radio, I realized the bulletin had already been aired earlier. The volume was turned up quite high, but I couldn’t move any closer. My feet froze where I stood. In that instant, my eyes went strangely dim—as though a shadow had fallen over them. Even with a crowd of people all around, I could see no one. All that floated before my eyes was the face of that motherly figure in the white saree I had seen once in the refugee camp.

I have recalled this image in many of my earlier writings: standing beside my father, both of us drenched under an umbrella in the torrential rain, watching her across the muddy stretch of Lobonhrod—today’s Salt Lake. I had not understood then why seeing that face evoked such strong emotions in me. Even after hearing the news of her death, even as tears welled up and blurred my sight, when her face appeared before me again, I still could not grasp why.

Today, I understand. When a child, surrounded by darkness, feels as if ghosts and demons are closing in, and in that suffocating fear suddenly catches sight of its mother, the fear dissolves at once, and hope returns. That white-sareed face in the refugee camp during 1971 was like that for young boys on the threshold of adolescence, our hearts quivering between terror and faith.

Beyond that emotion, much has been written about Indira Gandhi—her politics within India’s borders, her alleged authoritarianism, her political will, her personality, her humanity, her sternness as a stateswoman, and the contrasts between Jawaharlal Nehru’s democracy and her own. Many have also written about how even her political opponents, consciously or not, ended up following her path in some way.

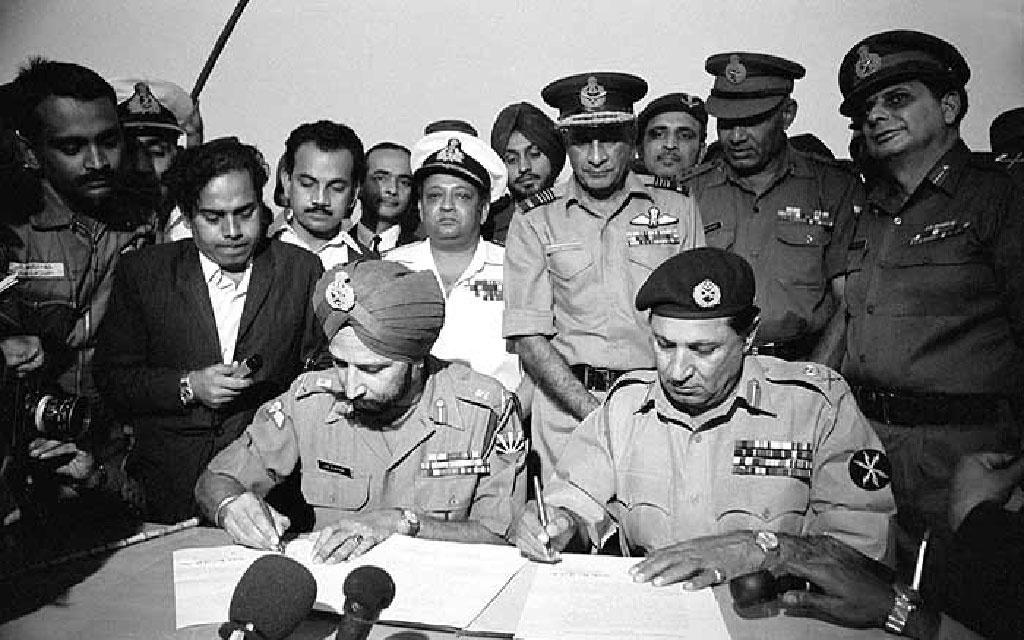

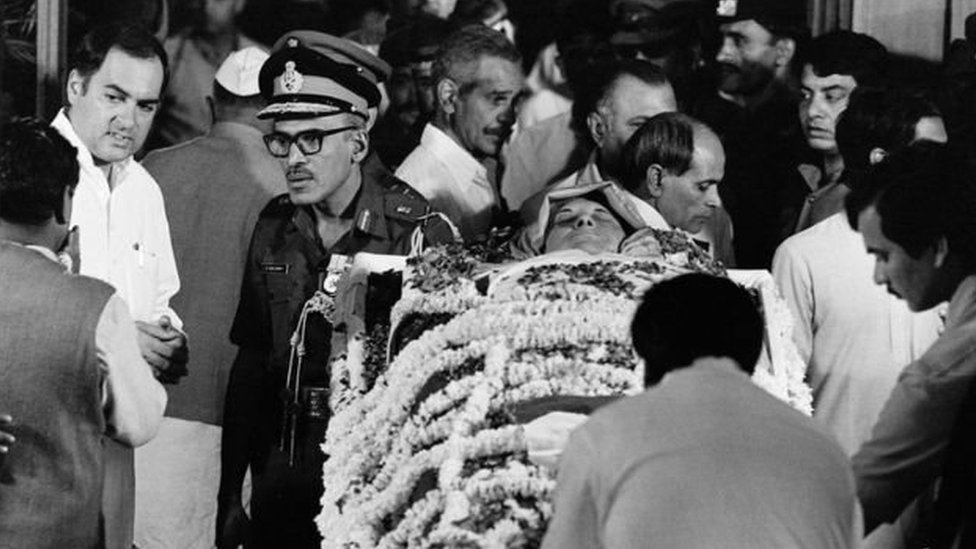

Yet, on this anniversary of her death, what comes to mind is not the political Indira Gandhi, but the woman who, through her life, proved that the soft power born of democracy, education, and, above all, family values, can become mightier than any army. In 1971, the granddaughter of Motilal Nehru, the daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru, and the student of Rabindranath Tagore—whom Tagore had lovingly named Priyadarshini—showed the world the full strength of that soft power. Within a mere twelve-day war, she oversaw the largest military surrender since World War II, and brought into being a new country—Bangladesh.

In that twelve-day war, she lost officers, soldiers, and ammunition. The sky thundered with bombers, the earth trembled with the growl of tanks—those sounds have been etched into our national memory.

But the Indira Gandhi who had grown up under family tutelage and within the intellectual companionship of Rabindranath had learned something deeper: the art of patience. And so, she took nine months to bring that war to its end—deliberately, calmly, and with a stateswoman’s foresight.

When the Mujibnagar government was formed in April, Pakistan had still not been able to bring in the troops it needed here. Because India had closed its air and sea routes, they had to come via Sri Lanka, which took them much longer. But Indira Gandhi did not calculate this war merely in terms of Pakistan’s weakness in weapons and logistics.

Rather, she made full, precise use of the three soft-power levers that Yahya’s mistakes and Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s success had placed in her hands. Only after she had used those to secure victory did she descend into a formal, armed war—with full ammunition—“to conquer the territory called Bangladesh and hand it over to Bangladesh.”

That last sentence is my own; I have placed it within inverted commas and set it apart because it can easily be misinterpreted, and therefore needs a little explanation. On the night of 3 December, when Pakistan attacked India in the western sector, India declared war on Pakistan. For this reason, the war is still recorded in history as the India–Pakistan War.

But before India declared war on Pakistan, Indira Gandhi had already won that war. She knew that, under the Geneva Conventions, Pakistan would have to surrender to India. And the moment Pakistan surrendered to India, East Pakistan, under international law, would be part of India.

However, Indira Gandhi, having already won the war, did not step in to end it as a conqueror—she stepped in as the midwife of Bangladesh. And so she did it lawfully. On the 4th, she formally united her Eastern Command with Bangladesh’s Mukti Bahini and recognized them as a Joint Command, and only then did she enter the war in the eastern theatre. On the 5th, at her request, Bhutan recognized Bangladesh. And on 6 December, she placed the recognition of Bangladesh before her own country’s parliament. She did all this so that even after Pakistan lost the war to India, there would be no legal barrier to this territory becoming Bangladesh, and India would have no claim over it. India had already recognized the country in its own parliament, and that recognition had been passed unanimously by all parties.

But before this recognition and before India’s direct entry into the war, three factors had already fallen into her hands: first, although the Awami League had won an absolute majority in Pakistan’s parliament—and had won almost every seat in the provincial parliament of East Pakistan—they were not allowed to form the government; instead, unarmed people were fired upon indiscriminately and a genocide was launched. Second, because of that genocide by the Pakistani rulers, ten million people took shelter in India as refugees. Third, Pakistan’s elected parliamentary leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (who, in law, was Pakistan’s prime minister and leader of the house), was arrested.

Indira Gandhi took these three issues and sent out, across the whole world, herself, her foreign minister, the leader of the opposition in parliament (later prime minister and BJP leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee), policy think tanks, artists, and even sportspeople, to build global public opinion against Pakistan’s genocide. A part of what she herself said in the many countries she visited can be found in India Speaks (if memory serves, that was the title), a book published by India’s Ministry of External Affairs.

On the other side, of the ten million people who had taken refuge in India, almost ninety percent were Hindus. Yet neither India, nor any Indian leader, least of all Indira Gandhi, ever said, “It is Hindus who have become refugees.” Western journalists tried again and again, but they could not get any Indian leader—and certainly not Indira Gandhi—to utter the phrase “Hindu refugees.” Instead, she was able to prove to the whole world that her poor country was having to bear the burden of shelter, food, medical care, and everything else for ten million Pakistani refugees.

And in building this public opinion, she never stopped at a hurdle. If a state did not stand by her, she went to that state’s people. For example, when her meeting with Nixon in America failed, she did not falter in the slightest. With complete composure, she went before university teachers and students. She spoke about the genocide in East Pakistan and about how Pakistan’s elected representatives had been prevented from forming a government. And in America, in the end, it was through this very soft power of public opinion that she won, again and again, larger numbers in the Senate and the Congress blocked the move to supply Pakistan with arms.

And ordinary Americans sent aid to the refugees; Senator Kennedy visited the refugee camps with a large group of journalists. American public opinion began to shift even more strongly against Pakistan’s genocide.

Meanwhile, although Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had been arrested on 26 March, India’s own parliament waited until August to speak about him. Only when Yahya initiated the farcical trial of Bangabandhu in a kangaroo court in August did things begin to move. And when that kangaroo court sentenced Bangabandhu to death, Indira Gandhi herself began telephoning heads of state, writing letters, and going on one foreign trip after another to build global public opinion against this sham trial.

It was then that she demonstrated, simultaneously, the power of her personal connections, her statesmanlike diplomatic outreach, and the moral authority of democratic India. She demonstrated how a leader can rise to great heights through a sense of timing, patience, and the effective use of language.

In November, it was not only that Yahya and Pakistan were forced to stay their hand from carrying out Bangabandhu’s sentence. In reality, by November, Pakistan had already lost to the global public opinion that Indira Gandhi had created. December’s war was then only a formality.

The Bengalis, as a nation, remain what they are. Rabindranath himself said, “You have kept us Bengalis—but not made us human.”

And our Bangamata—our Mother of Bengal—because she left us as Bengalis but did not make us human, we are the ones who demolish Bangabandhu’s house and then feast on biryani. And during the fiftieth anniversary of our independence, not a single poster bearing Indira Gandhi’s image was placed on the streets of Dhaka.

However, the timeless artist M.F. Husain has already immortalized the true history in one of his works: from the womb of Indira emerges the map and flag of our Bangladesh.

And in the memories of millions like us—or of many who have left this world carrying those memories—there remains that face in the white saree, the face of infinite patience.

That face comes to mind most vividly whenever, in any country of the world—not just anywhere, but even when I go to the capital of your country, Indira Gandhi’s country—I can say, “I am a citizen of Bangladesh.” And even then, that face returns to me: Indira Gandhi’s eternal, maternal face of endless endurance. The very face with which Rabindranath interpreted the nishkam dharma of the Gita—the selfless path of action. To truly understand that selflessness, he said, we must look closely at the faces of the mothers in our own homes.

Indira Gandhi was a politician, and as such, she will always be subject to criticism. In politics, there is no room for sentiment. Yet, when one connects her life to the freedom of the Bengali people and the birth of Bangladesh—when one remembers the refugee camps and the sea of blood of the Liberation War—then, on the anniversary of her cruel death, what returns to the mind of any grateful Bangladeshi is not politics but that motherly face.

The face in the white saree from the refugee camp.

(This article was first published in Bengali on Sarakhon.com, on 31st October 2025, during Indira Gandhi’s death anniversary. )

The writer is a journalist awarded the highest state honor, Editor of Sarakhon and The Present World.