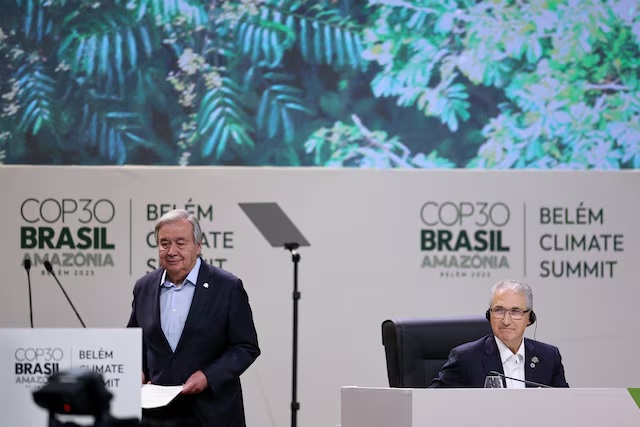

COP30 Draft Deal Drops Global Fossil Fuel Transition Plan

New text sidelines phaseout roadmap, intensifies North–South tensions

Negotiators at the UN’s COP30 climate summit in Belém have released a new draft deal that strips out language calling for a global plan to transition away from fossil fuels. The earlier version had included several options to guide countries in following through on a COP28 pledge to move away from coal, oil and gas. In the latest draft, unveiled before dawn on Friday, all direct references to fossil fuels have disappeared. That shift marks a major win for oil-producing nations that have resisted any wording implying a managed decline of fossil fuel production.

Dozens of countries—including Germany, Kenya and climate-vulnerable island states—had been pressing for a clear roadmap to operationalize the transition promise. They argue that without a shared plan and checkpoints, wealthy producers can keep expanding output while poorer nations shoulder the worst climate impacts. Saudi Arabia and other major exporters have pushed back, warning against language that could undermine what they call energy security and orderly markets. The draft text now leans heavily on vague references to existing obligations under the Paris Agreement rather than new, sharper commitments.

Finance, trade and fire-disrupted talks

The draft does, however, contain stronger language on funding adaptation to climate impacts. It calls for tripling global adaptation finance by 2030 relative to 2025 levels, reflecting growing recognition that countries need more support to prepare for extreme heat, storms and sea-level rise. But the text stops short of specifying who will pay, dodging the politically fraught question of whether rich governments must provide most of the money. Developing nations, which have long demanded predictable public finance rather than loans or private investment, are likely to see the paragraph as progress on paper but thin on guarantees.

Another notable section would launch a three-summit dialogue on trade and climate, bringing in the World Trade Organization and other bodies. That aligns with demands from countries such as China, which want carbon border tariffs and green industrial policies placed under multilateral scrutiny. It could prove uncomfortable for the European Union, whose carbon border levy has drawn sharp criticism from South Africa, India and others. The negotiating timetable has been further complicated by a fire at the summit venue earlier this week, which forced an evacuation and delayed talks for hours just as delegates were supposed to be narrowing differences.

Final hours, higher stakes

With the conference scheduled to end later on Friday, negotiators face a familiar last-minute scramble to bridge gaps between fossil-fuel producers, high-emitting industrial economies and climate-vulnerable states. Any deal must be adopted by consensus, giving resistant countries effective veto power over strong language on hydrocarbons. Diplomats say backroom discussions are focusing on whether some version of the transition roadmap can be reintroduced in softer form, perhaps folded into references to national climate plans. Others warn that pushing too hard could sink the entire package, leaving COP30 to be remembered more for chaos than progress.

Outside the talks, activists and Indigenous leaders from across the Amazon are denouncing the removal of fossil fuel language as a betrayal of climate science. They argue that without explicit commitments to wind down coal, oil and gas, promises on forests, adaptation and climate finance ring hollow. For frontline communities already facing floods, drought and wildfire, the stakes feel existential. Whether the final COP30 text restores any version of the fossil-fuel transition—or cements its erasure—will shape how historians judge this summit in the world’s largest rainforest.