Who Actually Governs Rakhine?

The Fiction of a Governed State

On paper, Rakhine appears to be a state under an identifiable authority, with the military government in Naypyidaw issuing administrative decrees, controlling borders, and signing agreements with Bangladesh. In diplomatic language, everything looks orderly: a central government, provincial administrators, civil bodies, and a supposed pathway through which the Rohingya might one day “return”. The communiqués describe a system that resembles a functioning state, one that is capable of guaranteeing rights and enforcing obligations.

None of this holds up when you turn the map over and look at the ground.

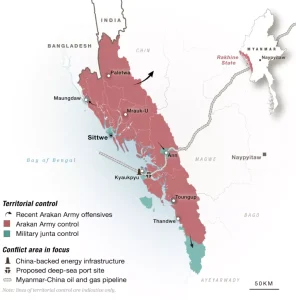

The real Rakhine is a region governed through overlapping and often competing centres of power. The Arakan Army (AA) controls most of the terrain, operating as a proto-state with its own administrators, courts, revenue collectors, and security structures. The junta survives in fragments: a few coastal towns, several bases, and a handful of strategic nodes that remain connected more by the memory of statehood than by actual governing capacity. Local commanders at checkpoints make up rules as they go. Rohingya communities organise their own survival networks, leaning on informal leaders, smugglers, and armed groups. And far above all of this float the outer powers—China, India, ASEAN, Bangladesh, the UN system—each with influence, none with full ownership of the reality on the ground.

To speak seriously about repatriation, the first obligation is to abandon the diplomatic imagination and recognise the administrative vacuum that actually exists. The question is no longer what the law says about Myanmar’s sovereignty over Rakhine. The question is, who can enforce anything at all.

A State That Survives Mostly on Paper

The Myanmar state’s presence in Rakhine is now more symbolic than substantive. Formally, it is the central government that signs repatriation deals, issues identity documents, and declares its readiness to receive refugees. Practically, it controls far less of the state today than at any time in the past decade.

Independent conflict monitoring and field reports converge on the same picture: the Arakan Army has pushed the military out of most of central and northern Rakhine. In some areas the junta’s authority has collapsed entirely; in others it lingers as a skeletal administrative outline without the capacity to govern daily life. Even signature events of statehood, such as the presence of regional commands or district administrators, have hollowed out. Earlier this year, international media carried images of the AA occupying a regional military headquarters, a symbolic moment that captured the scale of the junta’s retreat more vividly than any government denial could counter.

Where the junta still exists, it exists in fragments. Sittwe and Kyaukphyu remain under its control, but even there, governance is intermittent and dependent on the military’s ability to secure the immediate perimeter. Coastal corridors survive through force presence rather than legitimate authority. Highway checkpoints operate less as public institutions than as sites of extraction and suspicion. And through most of the rural interior, the government is little more than a memory—present in name, absent in function.

For the Rohingya, this produces an unavoidable contradiction: the state that Bangladesh negotiates with is largely absent from the areas to which refugees would actually return. A promise negotiated in Naypyidaw has little to do with the authority that controls the roads, fields, and camps in Rakhine itself.

The Structures of AA Rule

In the vacuum left by the junta, the Arakan Army has built its own governing order. It does not look like a conventional administration, but it functions with a coherence that makes it the dominant power across most of the region. In Rohingya-majority areas, however, this authority comes with a harshness that is increasingly well documented.

Human Rights Watch’s 2025 report paints a stark picture: movement restrictions, forced labour, coerced recruitment, arbitrary detentions, and severe limitations on access to food and healthcare. The stories of those who have fled AA-controlled zones describe an atmosphere of rigid control. The rule is disciplined but exclusionary, driven by a combination of military logic, ethnic nationalism, and an ingrained suspicion that treats the Rohingya as an inherently risky population.

The AA’s project in Rakhine has several overlapping layers, even if the organisation does not articulate them openly. It seeks to defeat or marginalise the junta and position itself as the defender of Rakhine interests. It is simultaneously building administrative structures—courts, tax systems, local administrators—to demonstrate its capacity for rule. And it is shaping an ideological narrative about who belongs in Rakhine, a narrative in which the Rohingya are often framed as outsiders rather than co-equal inhabitants.

For diplomats and aid agencies, this creates a difficult paradox. The AA is the actor that must be engaged if humanitarian work is to be possible in most parts of Rakhine. But it is also an actor involved in documented patterns of abuse that recall the behaviour of the very state it seeks to replace. Engagement becomes both necessary and deeply uncomfortable, because the practical gatekeeper is also a source of harm.

The map of AA control may appear neat when shaded on a screen, but the lived experience behind that colour is one of checkpoints, passes, interrogations, and conditional tolerance. The line between inclusion and exclusion is always thin, and for the Rohingya, usually drawn against them.

The Outer Ring: Power at a Distance

Step away from the frontline map and another geography appears, one that does not show trenches or checkpoints but flows of money, fuel, trade, and diplomatic language. Around Rakhine there is an outer ring of actors whose interests are intense, whose presence is constant, and whose relationship to the actual ground is curiously indirect.

In this ring sit China, India, Bangladesh, ASEAN states, and the UN system. None of them govern a township in Rakhine. None of them issue orders at local police posts. Yet they influence what is possible and what remains impossible.

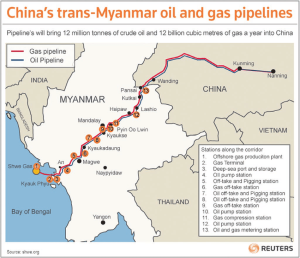

Rakhine’s location places it at the intersection of Chinese energy infrastructure, Indian connectivity corridors, and Bangladesh’s own security and humanitarian anxieties. For Beijing, the state is primarily a corridor: the path of pipelines, ports, and road links that shorten the distance between Yunnan and the Bay of Bengal. For Delhi, it is a buffer and a potential bridge, a space where fears about Chinese encirclement meet fears about migration and militancy. For Dhaka, it is a neighbouring territory that has failed to protect its minorities and exported the consequences as a permanent refugee population.

None of these vantage points are primarily concerned with Rohingya rights. Rakhine has become important as a route, as risk, as leverage. It is important as an energy corridor, as a piece of strategic depth, as a problem to be managed at the border. It is less important as a home that should be made safe for those who once lived there.

China’s approach reflects this clearly. It has no ideological loyalty to the junta or the AA. Its interest is in stability around infrastructure. If that stability is provided by a military regime, so be it. If it is provided by an entrenched AA administration that can secure pipelines and ports, Beijing can adjust to that as well. The question is not who governs Rakhine in principle, but who can credibly guarantee the safety of investments.

India’s posture is more ambivalent. It sees a risk in Chinese consolidation to its east and seeks connectivity of its own through the Bay of Bengal and onward into Southeast Asia. At the same time, the Rohingya have been framed within parts of the Indian political discourse as a security threat, especially in the northeast. Rakhine, from Delhi, can look like a zone where two anxieties overlap: apprehension about Chinese presence, and apprehension about cross-border mobility of a population already cast in security terms. That combination does not naturally generate a politics of protection.

Bangladesh sits in the most difficult position. It carries the everyday weight of the camps: the budget pressures, the political tensions in host communities, the policing concerns, the human lives condensed into narrow, crowded hillsides. It must maintain a working relationship with whatever authority sits in Naypyidaw, because diplomacy and regional norms demand it. At the same time, it understands that this formal counterpart is no longer the main actor in the places to which refugees might one day be sent back. Dhaka also has to navigate Beijing’s influence, recognising that Chinese relationships within Rakhine go far beyond what Bangladeshi diplomacy can easily reach.

The UN system and donors form another layer in this outer ring. On paper, they work within the grammar of protection and rights. In practice, much of their day-to-day engagement has shifted from the language of resolution to the language of maintenance. The Rohingya situation is increasingly treated as a long-term displacement to be managed rather than an emergency to be solved. Reports are written, mandates are renewed, programmes are reconfigured. The underlying balance of power that makes return unsafe remains largely untouched.

There is, in this outer ring, a persistent distance between influence and responsibility.

The Map That Repatriation Talks Refuse to See

Official repatriation discussions tend to lean on a map that no longer exists. They assume a coherent state authority in Rakhine, capable of guaranteeing security, administering citizenship, and managing disputes. They assume an institutional chain that runs from Naypyidaw to district offices to local police stations, and then down to communities. They treat the Rohingya as a population that can be slotted back into this architecture once a few conditions are negotiated.

The actual map makes these assumptions untenable.

Most of the territory is controlled by an armed movement that is not party to formal repatriation agreements, does not recognise the Rohingya as equal members of the polity, and has its own record of abuses against them. The central government that signs understandings with Bangladesh exercises only patchy influence over return areas, and in some districts, virtually none. Armed Rohingya factions, local militias, and informal brokers create further layers of coercion and dependency that no bilateral communique acknowledges.

Under these conditions, a repatriation deal negotiated solely between Dhaka and Naypyidaw becomes a kind of diplomatic theatre. It may ease immediate pressure on both governments by producing the appearance of progress. It may unlock or preserve certain aid flows. But it cannot produce the minimum baseline required for a refugee family to make a rational decision to return: a credible guarantee that the authorities controlling their home area will not abuse them.

When the Lines Move, the Answer Stays the Same

Rakhine is not static. Frontlines shift. The AA takes new positions or consolidates old ones. The junta loses ground, occasionally regains a pocket of territory, reasserts itself from the air. Local militias reorganise. Humanitarian access fluctuates as negotiations are made, broken, and remade. Each of these movements redraws the map slightly.

Outside the state, the outer ring responds in its own ways. Beijing recalibrates its language and its contacts to match who can best secure the infrastructure it cares about. Delhi adjusts its security posture along the northeast and revises assessments of Chinese reach in the Bay. Dhaka measures domestic pressures against regional relationships and the diminishing patience of host communities around the camps. Donors readjust budgets under the weight of multiple global crises, calculating how much can still be allocated to a protracted displacement with no clear endpoint. UN bodies update reports, renew mandates, and seek small procedural gains where larger structural change does not seem available.

With each adjustment, new “initiatives” can be announced. A fresh round of discussions, a pilot plan, a new task force, a technical committee. On paper, they suggest movement. On the ground, the core questions do not change.

Who actually controls the land to which people are supposed to return. How that control is exercised when nobody is watching. Whether any of the authorities involved are prepared to accept Rohingya as neighbours rather than as problems. And whether there is a credible mechanism that allows a family to look at all of this and decide that crossing the Naf again would be safer than staying where they are.

Most of the time, when those questions are asked plainly, the answer is still no. Not because the idea of repatriation is morally unacceptable, not because refugee communities prefer permanent exile as an abstract choice, but because the real distribution of power in Rakhine does not yet offer a pathway that can realistically be called safe or voluntary.