Rohingya Pathways Out: When Departure Becomes Address

Eight years on, Cox’s Bazar runs on routine, not alarms. The Rohingya do not move at random. They follow systems—old river channels, new fences, seasonal seas, paperwork both real and invented. The routes are stable enough to map; the outcomes are stable enough to manage. In the past eighteen months alone, officials and UN briefings count roughly 150,000 new Rohingya arrivals in Bangladesh—movement driven by a Rakhine state that remains unstable, and by a receiving apparatus on this side built to register and retain. (Al Jazeera)

Children are photographed, iris-scanned, and assigned birth documentation that is not citizenship but behaves like it. Clinics read camp IDs the same way they read district health cards. A lost card can be replaced faster than a stolen phone in Teknaf. Periodic “re-verification drives” promise accuracy, but their deeper effect is continuity: each renewal resets the clock of belonging. NGO staff speak of “beneficiary churn,” but churn barely exists; people age into the system faster than they exit it. Even those who leave for Malaysia often reappear months later—thinner, older, but already known to the database. Re-registration takes minutes. The apparatus never closes the file; it only updates it.

Eight years in, registration itself has become a form of quiet settlement. A person is counted, re-counted, and kept.

The Economy of Exit

Movement is expensive, and cost behaves like gravity. A foot crossing is cheap—two days of food, maybe a payment at a village checkpoint—but a sea berth is a year’s wages compressed into a single transaction. Markets inside the camps adapt. Gold bracelets are sold to middlemen who visit shelters the way micro-finance agents once did. Loans circulate through informal lenders in Teknaf bazaars; interest is not written but understood.

WhatsApp groups connect families in Malaysia to brokers in Ukhiya; 20,000 taka sent at midnight becomes a deposit on a boat seat by morning. Even failure feeds the economy. When passengers return after a push-back, they bring debt with them; repayment creates more labor, more movement, more risk. This economy does not slow displacement. It stabilises it. As long as debt exists, routes exist.

The border by foot

The border by foot

Along the Maungdaw–Teknaf belt, movement is granular and local. Families stage from village to hamlet, then to the last tree-line before the embankments. They wait for moonless hours and walk—ankle-deep through paddies, shoulder-deep through irrigation cuts—until the first Bangla voices answer back.

Guidance is intimate and practical: not cartels but neighbours-of-neighbours who know which culvert is passable, which embankment is patrolled, which footbridge washed out last monsoon. Fences and Border Outposts don’t close the route; they slow it. The effect is administrative—staggered arrivals, more night entries, registration queues at first light. Most of the ~150,000 who reached Bangladesh over the last eighteen months came by these land and short-river corridors, then entered the same queue at Ukhiya or Teknaf: name, father’s name, place of origin. (Al Jazeera)

The river as slipway

The Naf behaves like a conveyor: short crossings on low-freeboard boats, timed to slack tide and thin fog. Hulls are narrow skiffs with repurposed engines, sometimes a tarpaulin over bamboo hoops to flatten the silhouette. Payment is pooled—cash, pawned gold, an uncle covering the last berth because a baby is feverish.

Landings dissolve into silt bars and mangrove tongues; onshore, a cousin-of-a-cousin steers people to a madrasa courtyard or tea stall that knows whom to call. A brief river becomes a one-way threshold; once biometrics are taken in Cox’s Bazar, the file—and the person—settles. Field reporting and UN updates place these short-hop river/estuary entries within the same eighteen-month surge that Bangladesh has counted and registered. (UNHCR)

The long sea

After the rains, smugglers assemble larger hulls off Buthidaung or the southern Rakhine coast. One departure becomes three boats at sea—loads split beyond the horizon to avoid detection or to sell extra berths mid-voyage. The calendar is fixed: October through February is sailing weather.

Operations are minimal and improvised; a mother boat ferries people to smaller craft, fuel is rationed, water tighter still, and the GPS app on a teenager’s phone stands in for instruments. Interdictions produce long drifts and sudden rescues; push-backs are routine. The arithmetic is now documented as well as it is brutal.

So far in 2025, more than 5,300 Rohingya have embarked on these maritime journeys from Myanmar and Bangladesh, with over 600 recorded dead or missing—a ledger that under-counts boats with no mayday and no manifest. (UNHCR)

-

In May 2025, two offshore disasters off Myanmar were feared to have killed about 427 in a single weekend. (UNHCR)

-

In the first half of 2025, 1,088 people left Bangladesh by boat—about triple the previous year’s pace—including at least 87 children. (Save the Children)

-

In early November 2025, a split convoy from Buthidaung suffered a loss of at least 27 personnel near the Thailand–Malaysia border. (AP News)

Even survivors rarely return to Myanmar; those pushed back often re-enter the camps in Bangladesh. Departure still ends in residence.

The paper route

Not every journey is physical. Some are clerical. Inside Bangladesh, camp cards, ration books, and protection attestations open or close gates—food pickup, clinic access, police checkpoints. Outside the camps, a grey market of borrowed, bought or forged papers mirrors basic demand: to rent a room, see a doctor, take a bus, hold a job. Enforcement sweeps make headlines; the demand that created them remains. Paperwork builds a usable life, while formal repatriation remains hypothetical; the larger numbers above explain why the paperwork continues to expand to meet the increased arrival and prolonged stay.

The camp-to-sea pipeline

Cuts to rations and freezes on education and work entitlements set the sailing timetable months in advance. A neighbour who “made it to Malaysia” lights the trail on WhatsApp; an agent known only by a nickname names a price; a promise of factory wages justifies the debt. Gold bracelets are sold; loans are taken; remittances are pooled. Young men go first; families follow after a theft, a threat, or a clinic refusing a referral. The tally from January–June 2025—1,088 departures from Bangladesh, ~87 of them children—captures the structure behind the stories. (Save the Children)

Those who fail fold back into Cox’s Bazar. The attempt converts to permanence all the same.

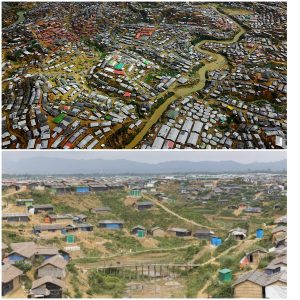

The camps that behave like towns

The camps operate like towns that refuse to call themselves towns. Streets have names, even if unofficial; markets have rhythms; disputes have mediators long before any police intervention. Routine is the architecture. Food queues run on weekly cycles; health posts open at the same hour every day; community schools teach basic literacy even when neither curriculum nor certification exists. Humanitarian agencies call this “service continuity”; for residents it is simply life. Children born in 2018 are now seven years old. They can name the stalls that sell the best shampoo, recognise which NGO logo means medicine day, and speak Bangla with the cadence of Cox’s Bazar.

The district has two economies—one Bangladeshi, one Rohingya—and both depend on each other. Vegetables from Ukhiya flow into camp markets; remittances from Malaysia flow back into Teknaf. Emergencies created permanence, and permanence produces systems.

Leaving to stay

Official language still points toward return; field practice points toward duration. The pathways—paddy, river, sea, and paper—are not provisional anymore. They are routines. People exit a province and enter an apparatus: registration, shelter allocation, periodic verification, school by another name, a clinic barcode that beeps like any citizen’s. What began as crossing becomes an address.

References

-

“At least 150,000 Rohingya refugees have arrived in Cox’s Bazar … over the past 18 months.” Al Jazeera, 11 July 2025. (Al Jazeera)

-

“Bangladesh has welcomed 150,000 Rohingya refugees in the last 18 months.” UNHCR, 11 July 2025. (UNHCR)

-

“More than 5,300 Rohingya refugees have embarked on dangerous maritime journeys … with over 600 reported missing or dead.” UNHCR/IOM, 11 Nov 2025. (UNHCR)

-

“About 1,088 Rohingya refugees embarked on sea journeys from Bangladesh during the first six months of this year, with around 87 of them children.” Save the Children, 15 Oct 2025. (Save the Children)

-

“Death toll from the sinking of a boat carrying Rohingya … rose to 27 … as bodies were recovered.” Modern Diplomacy, 11 Nov 2025. (Modern Diplomacy)