A war the Rohingya cannot afford

In the Rohingya camps and scattered diasporic pockets, the war in Rakhine is now experienced through short clips and forwarded messages. Facebook timelines and WhatsApp groups circulate videos of armed men moving through villages, badges blurred by low resolution or deliberate cropping. One day they are labelled as the Arakan Army, another day as “Rohingya mujahideen,” and by the weekend the same footage reappears under a new logo altogether.

People in the camps know better than most that much of this is propaganda. They have seen footage recycled, dates changed, and locations misdescribed. They have learned to be sceptical. Yet the steady flow of images shapes a broader perception that matters more than any single clip: that a new configuration of violence is emerging in Rakhine, and that the Rohingya are once again being drawn into it as political instruments.

For nearly a decade, the Rohingya story has been framed in a stark moral vocabulary. The sequence was simple and brutal: citizenship stripped, villages attacked, people forced across the border, Bangladesh and the international system scrambling to cope. The narrative revolved around a single crime and its victims. “Repatriation” became the official horizon — the phrase that allowed all sides to postpone harder questions about long-term futures.

That clarity is now eroding.

Power in Rakhine today does not belong to a single military authority. The Myanmar junta still holds key towns, garrisons, and airfields. Still, the Arakan Army has entrenched itself as the de facto authority across large parts of the state, collecting taxes, running courts, and setting rules of movement. In the spaces between them, older and newer Rohingya armed groups have begun to operate more visibly, claiming to defend their community against both state violence and abuses by other ethnic forces.

Meanwhile, conditions in the camps have deteriorated. International attention has shifted elsewhere; rations have been cut; education and livelihoods remain sharply constrained. A generation that crossed in 2017 as children has grown into adulthood in a suspended environment, with little to anchor them beyond family networks, religious institutions, and the digital echo chamber of a crisis that never quite ends. For many, the old language of peaceful return no longer carries conviction. Newer narratives — of self-defence, armed dignity, and “not waiting forever” — coexist uneasily with the older humanitarian framing.

This is where the idea of a three-way war comes in. Analysts and diplomats increasingly describe a possible configuration in which the Myanmar military, the Arakan Army, and a constellation of Rohingya armed actors all contest power and territory in Rakhine. On paper, this resembles a classic multi-sided civil war. In practice, it would be a conflict, as the Rohingya as a people are structurally unable to survive on their own terms.

For the junta, the temptation to cultivate Rohingya armed proxies is obvious. A handful of groups, nominally representing Rohingya interests but fighting primarily against the AA, offers a way to blur the memory of 2017 and reframe the conflict as a messy, multi-sided war. The same state that stripped the Rohingya of citizenship can then point to “Rohingya units” fighting under its umbrella as proof that the situation was always more complicated — a story of communal tensions rather than a targeted campaign of expulsion.

For the Arakan Army, an armed Rohingya presence is perceived through an entirely different lens, but also as a problem. The AA’s project is an ethnonational one: securing maximum autonomy over Rakhine as a Rakhine-led polity. In that vision, Rohingya communities are at best a tolerated minority, at worst a potential fifth column for the central state or transnational Islamist networks. Every group that appears even loosely aligned with Naypyidaw, or that deploys religious symbolism in ways that trigger existing fears, strengthens hardline views within the AA and among its civilian supporters.

Between these poles lie the fragmented Rohingya formations themselves, squeezed by expectation and suspicion from all sides. For some of their members and supporters, the turn to arms is framed as a belated assertion of agency — an end to pure victimhood, a signal that Rohingya lives will no longer be lived entirely at the mercy of others. For others, it is part of an older story of facilitators and patrons trying to reinsert themselves into a changing conflict economy. What these groups lack is what both the junta and the AA still possess: recognised, defensible territory and political leverage. There is no Rohingya-administered zone in Rakhine. There is no secure rear. Only a patchwork of villages that can be contested, exposed corridors along rivers and roads, and across the border, a set of camps on land controlled by a state that has repeatedly said it does not intend to integrate this population.

From a distance, the three-way war can be drawn as a neat triangle: junta, AA, Rohingya groups, each at a vertex. On the ground, that geometry breaks down. One point is a weakened but still heavily armed state with air power and international recognition. One is an ascendant insurgent movement that increasingly functions as a proto-state. The third is a stateless community whose armed outgrowths can be courted, disowned, and sacrificed by the other two without altering the balance of power.

This is why a Rohingya-versus-AA insurgency, or any sustained confrontation between Rohingya fighters and Rakhine forces, is almost guaranteed to end badly for ordinary civilians. The AA holds local legitimacy among much of the non-Rohingya population, tight command structures, and growing experience in governance. The junta, even as it loses ground, retains the capacity to bomb and shell. Rohingya fighters would be operating in areas where neighbouring communities have been taught for decades to view them with fear or hostility, and where every attack attributed to them risks triggering collective punishment.

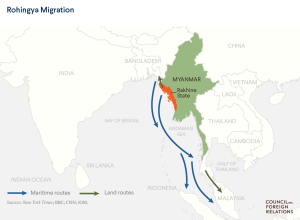

From Dhaka’s perspective, this emerging map is a security nightmare rather than an analytical exercise. Each spike in fighting along the Maungdaw–Buthidaung axis, each report of AA–Rohingya clashes or junta airstrikes, has direct implications for Bangladesh’s border management and internal politics. A few badly aimed shells or a sudden rush of boats can force the government into impossible choices: allow new arrivals and face domestic backlash, or push people back toward active conflict zones and absorb the moral and diplomatic cost. Bangladesh bears the full humanitarian burden while controlling none of the variables inside Rakhine.

Inside the camps, the three-way war scenario deepens pressure to securitise. If Rohingya armed groups are perceived — fairly or not — as recruiting from camp populations or using Bangladeshi territory for logistics, any state apparatus will respond with restrictions and surveillance. That may reduce immediate risks but also hardens the camps into spaces of suspicion, undermining what little trust remains and increasing the appeal of clandestine networks offering escape through dangerous migration routes.

More fundamentally, this evolving geometry erodes the official horizon of “safe, voluntary, sustainable repatriation.” In theory, all actors still repeat the formula. In practice, a Rakhine landscape divided between the AA and a desperate junta, with Rohingya armed groups caught in between, is not a landscape to which mass civilian return is realistic or responsible. A community cannot be repatriated into a theatre where it is simultaneously courted as a proxy, suspected as a traitor, and punished collectively for the actions of small armed factions. Nor can it expect international guarantees of safety when no single authority is capable of enforcing them across the areas where Rohingya once lived.

The three-way war scenario is therefore not just a military risk; it is a political point of no return. Once the conflict in Rakhine is widely understood as a triangular contest in which Rohingya groups are one of the actors, the global moral clarity around 2017 fades. The appetite for sustained pressure on Myanmar weakens. The argument for a large-scale, rights-based return becomes even harder to sustain.

History, however, does not freeze in the camps. It accelerates in other directions. As formal repatriation slips further out of the realm of credible policy, two quieter trajectories become more visible: gradual, informal assimilation into host societies like Bangladesh, and onward movement along irregular migration routes to countries like Malaysia. Neither path is clean, safe, or just. Assimilation in Bangladesh is occurring without legal status, in the shadows of labour markets and urban slums. Onward migration exposes people to smugglers, detention, shipwrecks, and exploitation. Yet for many Rohingya, these paths are beginning to feel more tangible than a promised return to a Rakhine now being reshaped without them.

Against this backdrop, the notion of a three-way war is less an analytical frame than a warning — a glimpse of a future in which the Rohingya cease to be primarily a question of justice and become a set of security variables instead, and migration flows are to be managed. What disappears, quietly, is the possibility of return: not only as policy, but as an imagination the community can still afford.