Ozone layer on track to heal thanks to decades of global cooperation

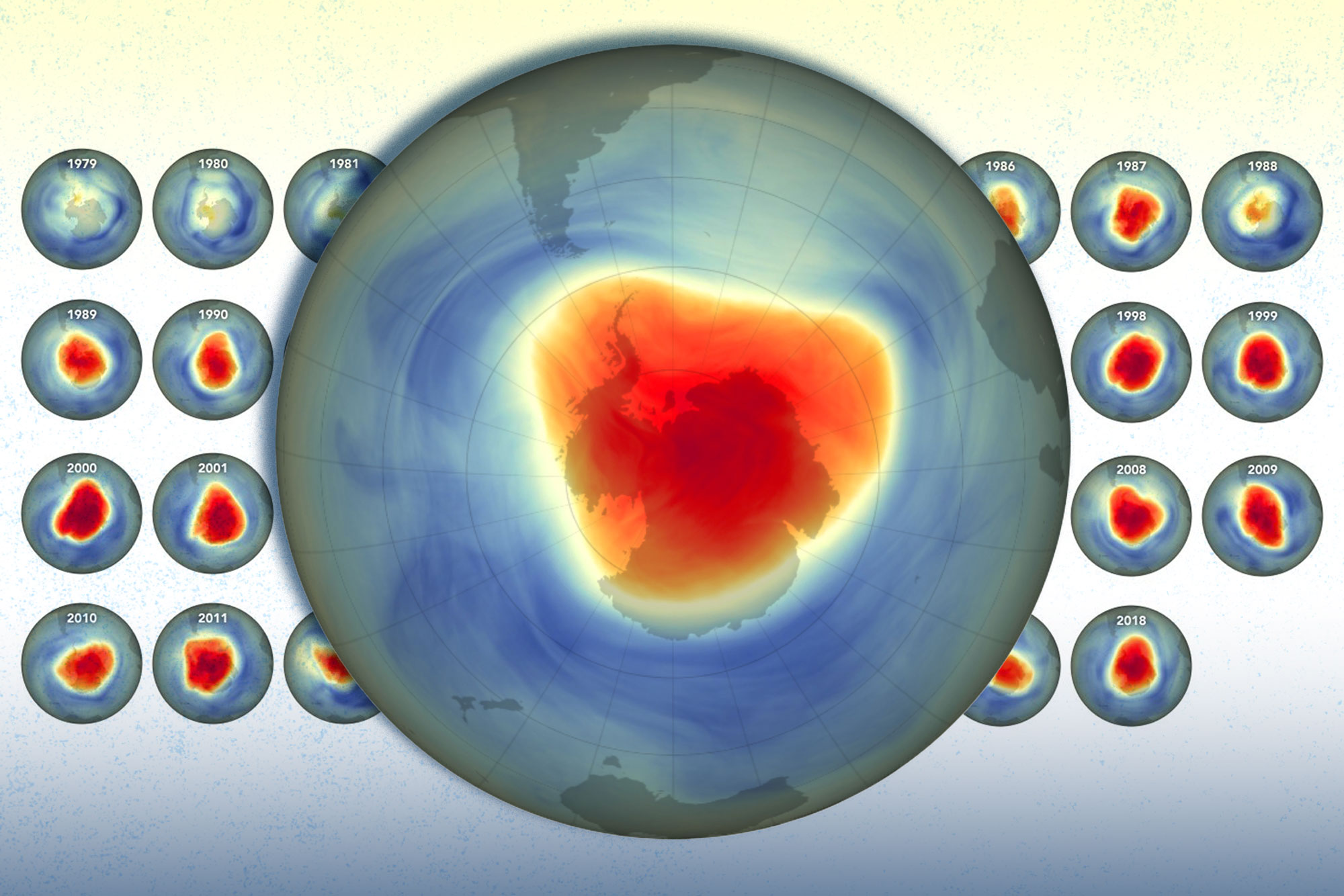

UN report says Antarctic ozone hole could close by 2066, with recovery elsewhere even sooner

A new assessment released on January 9 by the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organization brings encouraging news for the planet’s protective shield. Scientists found that concentrations of ozone‑depleting chemicals have fallen enough that the stratospheric ozone layer is on course to return to pre‑1980 levels within the next four decades. Over Antarctica, where an annual “ozone hole” forms each Southern Hemisphere spring, full recovery is projected by around 2066. The Arctic is expected to bounce back by 2045, while mid‑latitude regions could recover as early as 2040. The progress is the result of the Montreal Protocol, a landmark 1987 treaty that banned chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other industrial chemicals that destroy ozone molecules. The new report notes that roughly 99 percent of those substances have been phased out, preventing an estimated 135 billion tonnes of carbon‑dioxide equivalent emissions.

Ozone sits 15 to 30 kilometres above the Earth’s surface and absorbs most of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. When the layer thins, more UV light reaches the ground, increasing risks of skin cancer, cataracts and crop damage, and disturbing marine ecosystems. The 2026 assessment emphasizes how quickly humans responded once they realised the threat. CFCs were introduced in the 1930s as refrigerants and aerosol propellants. In 1974 scientists Mario Molina and Sherwood Rowland warned that CFCs could deplete the ozone layer; in 1985 British researchers announced that an ozone hole was appearing over Antarctica. Public concern prompted governments to negotiate the Montreal Protocol just two years later. Subsequent amendments accelerated the phase‑out and added chemicals such as hydrochlorofluorocarbons and methyl bromide. The report also credits developing nations with adhering to strict timelines despite initial fears about economic impacts.

Lessons for climate policy and the road ahead

Environmental leaders point to the ozone story as evidence that coordinated global action can solve seemingly insurmountable environmental problems. Petteri Taalas, secretary‑general of the WMO, said the success of the Montreal Protocol sets a precedent for tackling greenhouse gas emissions. Unlike CFCs, carbon dioxide and methane come from a wide range of sources—including power plants, transportation, agriculture and deforestation—making mitigation more complex. Still, the ozone story shows that banning harmful substances can spur innovation in safer alternatives. Many refrigerants now use hydrofluoroolefins or natural coolants; companies have redesigned manufacturing processes; and consumers barely notice the changes. According to Quartz’s coverage of the UN report, phasing out ozone‑depleting chemicals has already slowed climate change because those substances are potent greenhouse gases themselves.

However, scientists caution that recovery is fragile. Illegal production of banned chemicals has occurred in the past, and warming temperatures could alter atmospheric circulation, affecting ozone dynamics. Continued monitoring is essential to detect any setbacks. There are also open questions about the use of geoengineering techniques such as injecting aerosols into the stratosphere to cool the planet; some methods could harm the ozone layer. The report’s authors urge policymakers to treat the ozone treaty as a model while recognising that the climate crisis demands even broader cooperation. As the world races to reduce carbon emissions to net zero by mid‑century, the healing ozone layer offers a rare success story—and a warning that progress comes only through sustained, collective effort.