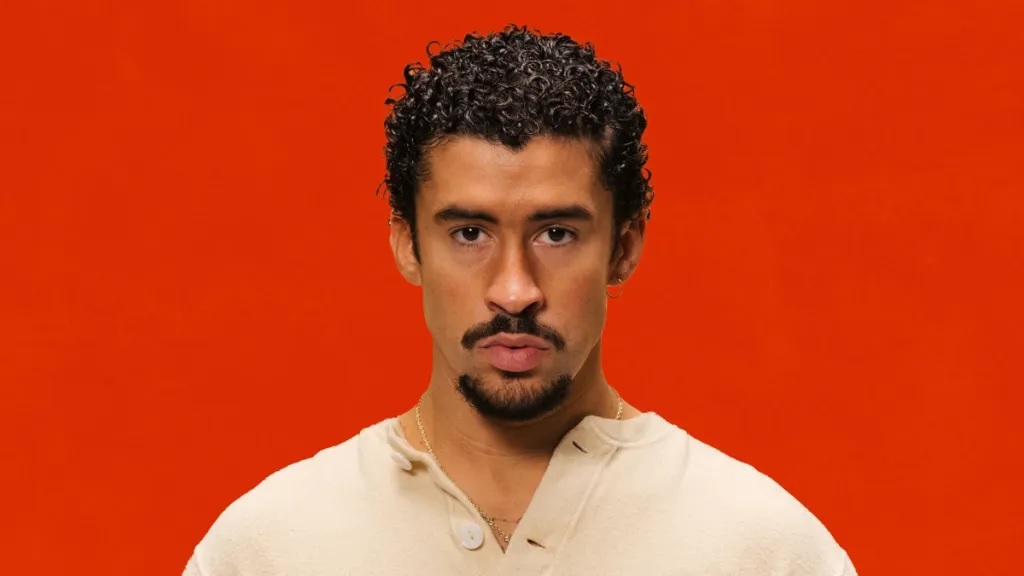

Bad Bunny faces $16 million lawsuit over unauthorised voice sample

Singer accused of using former classmate’s vocal line without permission

Puerto Rican superstar Bad Bunny is facing a $16 million lawsuit from a woman who claims her voice was used without permission on two of the singer’s hit songs. In a complaint filed in Puerto Rico and reported on January 9 by Rolling Stone, Tainaly Y. Serrano Rivera alleges that she recorded the phrase “Mira, puñeta, no me quiten el perreo” (“Look, damn it, don’t take away my perreo”) at the request of producer Roberto Rosado, also known as La Paciencia, in 2018 when they were theatre students. She says she believed the recording was for a class project, not a commercial release. The line later appeared on Bad Bunny’s 2018 song “Solo de Mi” from his album X 100pre and again on “EoO” from his 2025 album Debí Tirar Más Fotos, becoming a signature chant at concerts.

Serrano claims she never signed a contract granting Rosado or Bad Bunny permission to use her voice. She argues that the phrase has become synonymous with the Grammy‑winning artist, who has used it to sell merchandise and build his brand. Her attorneys, José M. Marxuach Fagot and Joanna Bocanegra Ocasio, previously represented Bad Bunny’s former girlfriend Carliz De La Cruz Hernández in a 2023 lawsuit that accused him of using her voice on other recordings without consent. That case wound through both federal and state courts and has yet to be resolved. In the new lawsuit, Serrano is seeking $16 million in damages for violations of her privacy and publicity rights.

Rights disputes highlight growing tension over sampling and consent

The case shines a light on the increasingly contentious issue of sampling and consent in the music industry. Advances in digital technology have made it easy to record, manipulate and sample voices, but legal frameworks for compensating contributors have not kept pace. Serrano’s complaint states that her phrase has been repeatedly played at concerts and prominently featured on merchandise, generating substantial revenue for the artist and his label, Rimas Entertainment, while she received nothing. Bad Bunny, whose real name is Benito Antonio Martínez

Experts say the lawsuit could set an important precedent for how courts handle cases involving non‑celebrity contributors to popular music. Sampling disputes are common in hip‑hop and electronic music, but vocal phrases recorded informally by friends or classmates rarely end up at the centre of high‑profile legal battles. If the court finds in Serrano’s favour, it could encourage musicians and producers to obtain clear, written agreements even when working with acquaintances. Record labels may also re‑evaluate their clearance processes to avoid costly lawsuits and reputational damage. The case is drawing comparisons to previous disputes over voice rights, including the 2023 claim by Bad Bunny’s ex‑girlfriend, which remains unresolved.

Beyond the legal questions, the suit raises broader ethical issues about recognition and compensation in creative industries. Fans often assume that catchy phrases and vocal hooks originate with the featured artist, overlooking the contributions of lesser‑known collaborators. Serrano’s story underscores how an offhand recording can become a global catchphrase without the speaker’s knowledge or benefit. As streaming platforms drive demand for new music and social media amplifies catchy lines, the potential for disputes grows. Musicians may now need to treat all recordings, no matter how casual, as potential commercial assets.

Bad Bunny’s popularity has skyrocketed since his debut, and he has been Spotify’s most‑streamed artist multiple times. He is currently preparing for a new world tour and promoting his latest album. The lawsuit arrives at an awkward moment, forcing the artist to balance public relations with legal strategy. Industry observers note that while fans may continue to support him, the case could influence how artists engage with collaborators. As debates over intellectual property intensify, the outcome of Serrano’s claim may resonate far beyond one reggaeton star’s tour, shaping the rules of engagement for a generation of creatives.