Will “Muradnagar’s Draupadi” Find a Place in the July Museum?

In This Country, Can a Woman Ever Be Safe Again?

On Saturday afternoon, I visited the home of a younger brother. He’s incredibly wise and deeply patriotic. Engrossed in our conversation, I didn’t realize it was already 11 p.m. Amidst our discussion, his wife—an educated woman and a portrait of a loving mother and sister—brought me a mango and said, “Dada, please give this to Boudi (your wife).”

At that moment, I recalled Tagore’s words: that women are like gravity, holding families and society together. Without them, men would be like clouds drifting in the wind, unable to build a society or a home. As we talked, the faces of my late mother and sister floated before me.

While returning, I carried not just a mango, but the love of a sister in my heart. Sitting in the car, I glanced at my phone—dozens of missed calls and messages. (My phone was on silent.) All of them were from my journalist juniors. Every message was a video titled “Hindu Woman from Muradnagar…”

I opened one and immediately had to close it.

Back home, I didn’t even remember to take off my clothes. My son kept insisting, “Dad, it’s almost 1 a.m. Please eat, your acidity will get worse.” He’s an adult now, like a friend. We talk about everything under the sun. But even to him, I couldn’t speak about what I saw—nor could I believe it myself. Was it real?

I forwarded the video to a few trusted juniors and asked, “Is this real?” Many replied with a short report from BDNews24. Others started sending me posts from social media—statements from the victim’s family, accounts from those who rescued her.

My body began to shut down. I couldn’t think. In desperation, I even called a 74-year-old past midnight.

I couldn’t sleep the entire night. The sun hadn’t risen yet, but I couldn’t stay in bed. I slowly made my way to the reading room. No, I can’t say I was calm—but I kept wondering:

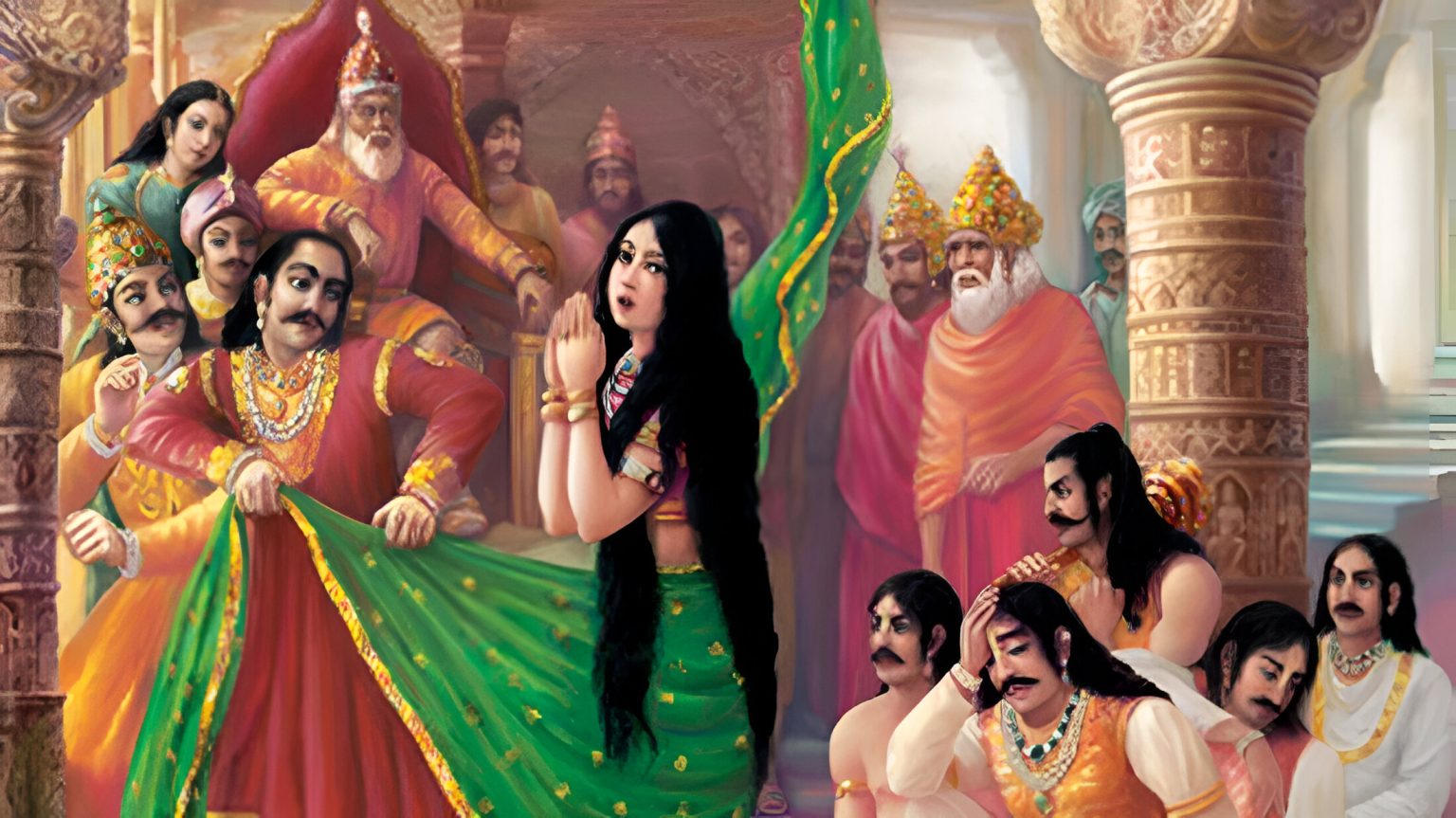

Did Draupadi’s disrobing happen in this world?

Did an old, blind king named Dhritarashtra really allow Draupadi to be stripped because of his lust for power? Is it then true that when kings become blind with greed, Dushasana emerges—and Dushasana means the unchecked right to violate Draupadi?

At such times, are women no longer mothers or sisters?

When power is seized through deceit—what we now call “meticulous design”—women become unsafe. The game of rigged dice, once played in ancient courts, has now become a tool of modern statecraft.

And even if an era passes after Draupadi’s disrobing, Bhim will still drink Dushasana’s blood. That’s what history teaches us—again and again.

Who Protects the Women?

But as I write this, I wonder—

Is it only Draupadi being disrobed?

What about those leaders and thinkers of the recent anti-government People’s Uprising? The audio leaks we’re now hearing about their female colleagues—are those words fit to be heard? Were those women not someone’s sisters, not someone’s daughters?

This feels like the state after Arjun lost his Gandiva—the collapse of heroism. When Krishna’s clan women were attacked, Arjun tried to bring them to safety in Hastinapur, but lower-caste raiders abducted them.

From Muradnagar’s horrors, to the vulgarities against female companions of movement leaders, to the insults hurled at women on the streets, to the black paint thrown on their bodies—it all leads to one question:

If things go on like this, will any woman in this country—especially a Hindu minority woman—ever be safe?

A Society’s Shame

The image of the Hindu woman from Muradnagar, trying to cover her naked body with her white, bangle-wearing hands, silenced the conscience of anyone who still has one. Even I couldn’t sleep. And yet, it wasn’t unexpected.

Just two weeks ago, a major industrialist, whose factories span several cities, told me during his regular site visits, “Dada, you have no idea. In the suburbs, rape has become even more terrifying than extortion. And if the woman’s a minority—forget it.” He even named parts of Dhaka where women are no longer safe.

The Muradnagar incident happened on Thursday night. And that very Thursday afternoon, a Hindu woman messaged me: “Dada, I can’t take it anymore. If nothing is going to change, suicide seems like the only answer.”

At the time, I thought—maybe she’s reacting to routine pressures faced by minorities. Maybe it’s just extortion, maybe threats. But that industrialist’s words proved hauntingly true.

Beyond Majority and Minority

In reality, this isn’t about minority versus majority. The final truth is Bangladesh itself.

Will this country’s culture fall into the hands of such depraved men—who know no culture beyond a woman’s body and their beastliness?

In Sri Lanka, too, there was a People’s Uprising. But those who stormed the presidential palace didn’t steal anything. No one danced with a woman’s undergarments.

And yet, the images the world now sees of Bangladesh’s uprising show ducks, fish, tattered carpets being stolen, and men dancing with women’s lingerie.

Sri Lanka returned to normal within a month. But in our country, mob violence is only growing. And along with it, the disrobing of “Muradnagar’s Draupadi,” the vulgar audios of movement leaders, the obscene dances with women’s underwear.

Bengali Culture in Decline

The Bengali is not a civilized race like the Iranians. In Iran, even if a husband gifts underwear to his wife or vice versa, they wrap it modestly. They don’t present it openly.

But Bangladesh? The whole world knows what it has seen.

The Economist recently wrote that the dream of Bangladesh’s liberation war died within four years. They titled their piece on the July Uprising as “Bangladesh’s Blunder” and said it was dead within a year.

At this stage in life, having seen both sides of the coin, I believe that the reason the liberation dream didn’t last beyond three and a half years isn’t just due to anti-liberation forces. It was also because of the behavior and frenzy of some post-war freedom fighters themselves.

That’s why those building the Liberation War Museum in Bangladesh must include both sides of the story. Without that, the museum will remain incomplete, and history will stand on hollow ground.

The Museum Must Be Whole

Likewise, I’m hearing that Ganabhaban (Prime Minister’s Residence) may be turned into the July Museum. I won’t comment on how appropriate that is for a future elected government. But wherever this July Museum is built, if it is to be complete—

It must contain not just memories of the past regime’s cruelty, or the narrative this government wishes to preserve. It must also include:

- The statue of the man dancing with underwear,

- Those who stole ducks, fish, vegetables, bags, and clothes,

- The leaked audio of movement leaders speaking to their female companions,

- And the video of “Muradnagar’s Draupadi” being disrobed.Without all of that, can this proposed museum ever be complete?

Author: National Award-winning journalist; Editor, Sarakhon and The Present World