“Yes–No” Votes and the Days of Canal Digging

It is 30 May 1977. I am sitting in the school field of a remote village in Barishal. Noon is slowly approaching. As far as the eye can see, it feels like two lines from a poem by the poet and scholar Syed Ali Ahsan:

“In the intimacy of many leaves

a profound grove.”

Every country on earth is beautiful. Even deserts possess a beauty of their own that no green foliage can replicate. Yet one’s birthplace holds a different kind of affection for everyone. East Bengal—today’s Bangladesh—naturally carries a special tenderness for any Bangladeshi Bengali. Even so, what one understands as East Bengal was embodied most intensely, at one time, by Barishal itself—a lush, serene maiden of a land.

So much green, so much water, such a pure sky—it did nothing but spread enchantment.

Perhaps that enchantment felt deeper because I was roaming the plains and outskirts of Barishal with an unusual lightness of mind at the time.

In any case, as the midday sun began to slope, I sat down in the shade of several large trees lining the edge of the field. There was no one else to be seen on the ground.

After four in the afternoon, I suddenly noticed a few policemen and several other men coming out of the school rooms and going back inside.

I was no criminal. In fact, that journey of mine was essentially the journey of a good student within institutional boundaries slowly becoming a bad one. So I felt no fear at all. With a light heart, I moved forward slowly.

The moment I stepped onto the school veranda, I realized that some kind of voting was taking place—or had already taken place. The men in plain clothes with the police were mostly schoolteachers. They were the presiding officers of the vote.

One fine quality most teachers—from schools to universities—once had was that they could unhesitatingly assume anyone to be a student and order them around accordingly. Seeing me, one teacher, speaking in the Barishal dialect, asked whether I knew arithmetic. Thinking of the respect I owed to Sejdada, who had taught me mathematics, I could not say no. The teacher then called me into one of the school rooms.

Inside, I saw voting booths set up for the election. Outside, several ballot boxes were stacked in one place. In those days, ballot boxes were black. Sheikh Hasina had not yet led the movement that would later compel the Election Commission to adopt transparent ballot boxes.

I noticed that the ballot boxes stacked nearby were marked “Yes,” while those placed farther away were marked “No.”

The task the teacher assigned me was roughly this: calculate how many “Yes”-stamped ballots needed to be removed from the total so that voter turnout would appear slightly above 80 percent, and the percentage of cast votes would exceed 90 percent. For such arithmetic, one hardly needs Jadab Babu’s Arithmetic. I did the calculation quickly. The teacher was very pleased. He also informed me that he taught Bengali and knew grammar very well. His father—some Chakraborty (I have forgotten the exact name)—had been a teacher of Sanskrit grammar.

Without prolonging the conversation, I offered my salutations and set off toward a friend’s house. On the way, beside the Ice Cream Factory, ice cream was being sold on bamboo sticks. I bought one and kept walking, licking it as I went.

It became clear to me that the “Yes–No” vote of President and Chief Martial Law Administrator Major General Ziaur Rahman had concluded that day. And through this victory, he had obtained legitimacy to govern the state.

At that time, along both sides of Barishal’s earthen roads, there were not only canals brimming with clear water, but also a combined fragrance of leaves and flowers from countless trees. The nose absorbed that scent, and the “Yes–No” vote slipped away from the brain’s cells.

That year, rainfall was heavier than usual from June onward. Ramadan seems to have fallen in August or September. In those days, all of Bangladesh’s cities—large and small—were as green as villages. By early autumn, a chill would descend onto the leaves.

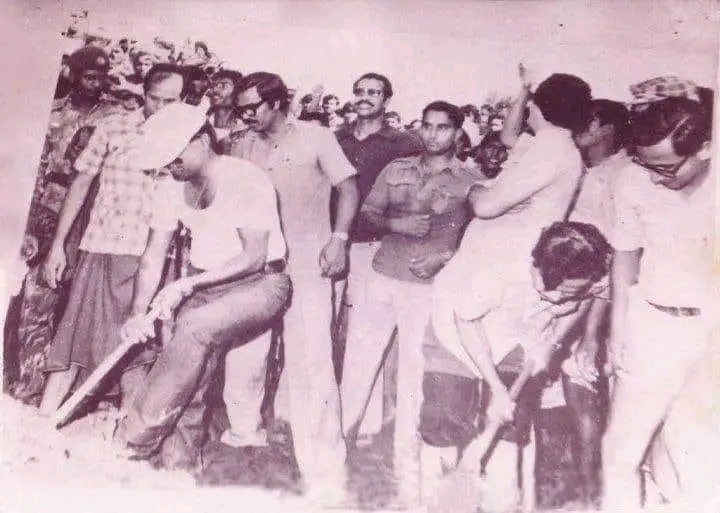

On one such morning, filled with light mist and a sweet scent of winter, in a sub-divisional town of the then Khulna district (greater Khulna), the actress Bobita and several film and radio artists were scheduled to come to dig a canal. At that time, the fact that radio artists were considered on par with film stars may sound unbelievable today. Although Bobita had been a major actress since childhood, she felt less like a silver-screen figure and more like someone from among us.

I thought I would go see her dig the canal as well.

The canal digging was scheduled for 9 a.m., but delays due to helicopters or something else, along with everyone’s makeup arrangements, meant that it was almost eleven by the time things got going.

Then a problem arose: there was no canal suitable for digging. This was a tidal region. Nearly all canals were full of water. So a decision was made to cut earth from the bank of a beautiful, water-filled canal—its curves like a thick braided plait of hair—flowing alongside a paved road near a prominent college, and pile the soil onto the roadside slope.

The whole thing felt strangely like a scene from a film shoot. I kept missing the absence of director Alamgir Kabir Bhai.

Meanwhile, across the road at some distance, I noticed a few senior college teachers standing together. In those days, most good colleges were still private, and the teachers were senior figures. Among them lingered a distinct demeanor reminiscent of British-era Presidency College and University of Calcutta graduates.

I got off my bicycle, rested my hand on the handlebars, and walked closer to the teachers. I greeted them and stood there. In those days, sub-divisional towns in Bangladesh regularly received Time, Newsweek, Far Eastern Economic Review, India’s The Week, and various academic journals. Teachers formed a large readership for these publications. Coaching batches had not yet become the norm. NGO consultancies had not arrived. As a result, teachers were often seen in the afternoons at bookshops, magazine stands, or current-affairs corners.

Because of this, any discussion teachers had, anywhere, became a classroom for students. Standing at a distance, I heard one of the teachers say that no matter how much India maintained contact with Ziaur Rahman, he knew he would not be able to conclude a Ganges water treaty. India would not sign such a treaty with him. India is a tough country. Ziaur Rahman was also a clever man, which is why he introduced the canal-digging program for the people.

Another teacher immediately added that among Pakistan’s two former parts—including today’s Bangladesh—the most vulnerable position was with respect to India’s inherent water power. One part lay downstream of the Indus basin, and we lay downstream of the Ganges and Brahmaputra basins. Therefore, water power was in their hands.

The teachers’ conversation drifted elsewhere. Time passed.

By then, even the communists had withdrawn from the canal-digging program. Mani Singh’s support for Ziaur Rahman through canal digging had come to an end. Around that time, a story circulated among politicians in Mymensingh town. The story went like this: Awami League leader Tofail Ahmed was still in Mymensingh jail. One day, Mani Singh, newly arrested, was brought there. Seeing him, Tofail Ahmed remarked in his characteristic manner, “Why are you here, Mani Da? Is the canal digging finished?”

When I later asked Tofail Ahmed about the truth of this story, he smiled faintly.

Author: Recipient of the highest state honor, journalist; Editor, Sarakhon; The Present World.