Climate change and La Niña blamed for Southern African floods

Study links extreme rainfall to climate change and La Niña

A new analysis by the World Weather Attribution group blames a combination of human‑driven warming and the natural La Niña cycle for the catastrophic floods that swept across Mozambique, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Eswatini at the start of 2026. Researchers compared rainfall records with those from the pre‑industrial era and found that the region’s extreme downpours are now about 40 percent more intense. The warming of oceans caused by greenhouse‑gas emissions means the atmosphere can hold more moisture; when La Niña’s cooling pattern in the Pacific naturally brings wetter weather to southern Africa, the result can be torrents of rain that overwhelm infrastructure. In some communities, more than a year’s worth of rain fell in a matter of days, washing away homes and destroying crops. At least 200 people were killed and hundreds of thousands more displaced. South Africa’s Kruger National Park closed after swollen rivers damaged bridges and roads, and repair costs are expected to run into the millions of dollars. The study notes that the current La Niña cycle is weak, yet warmer‑than‑normal seas have still amplified rainfall, signalling that climate change is already shifting baseline conditions.

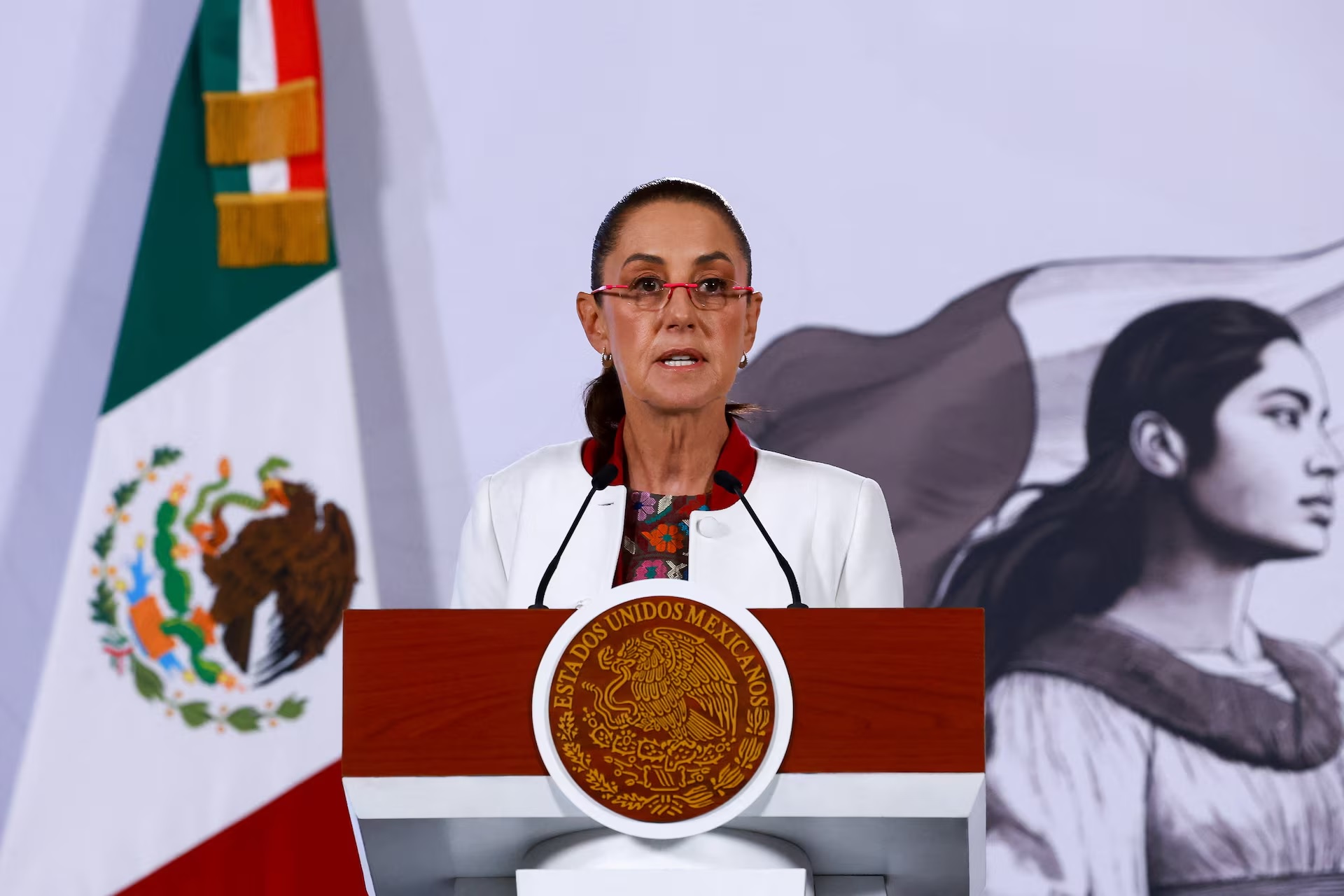

The report’s authors warn that such disasters will become more common unless nations rapidly reduce fossil‑fuel use and help vulnerable communities adapt. Co‑author Izidine Pinto said human‑caused warming is “supercharging rainfall events”, adding that without major emissions cuts, storms of this magnitude will occur with increasing frequency. He urged governments and aid agencies to invest in flood‑resilient infrastructure, restore wetlands that can absorb excess water and develop early‑warning systems. Communities must also adapt agricultural practices to withstand erratic weather, he said. The researchers argue that wealthier countries, which bear most historical responsibility for greenhouse‑gas emissions, have an obligation to fund adaptation in places like southern Africa. They also caution that La Niña can heighten the risk of drought in other regions, underscoring the need for comprehensive climate strategies. As the Southern Hemisphere braces for more extreme weather, the study serves as a stark reminder that the effects of warming are no longer theoretical. Policymakers must weigh the cost of climate inaction against the human toll of disasters that are already here.